Murghab – Life in Murghab

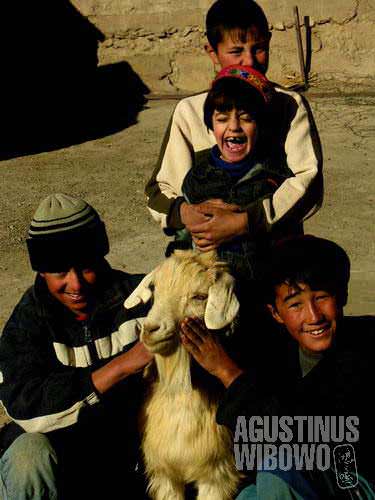

A morning greetings from Murghab

Murgab (Murghab) was promising when it was built. It was a new Russian settlement built as frontier city of Pamir. The highway connecting the isolated mountains to the lowland towns was supposed to bring wealth to the nomadic community. Life had changed ever since. A town was built on the top of mountains. People were educated. Frontier military checkpoints were enforced. But how is life now, after Tajikistan gained independence from the USSR and civil war took place in the new country? The hope of the future had turned to be a bad fate.

I had got a chance to know Gulnara, a 54 year old woman working as a primary school teacher in Murgab. Gulnara is the younger sister of Khalifa Yodgor from Langar. But the last time she saw him was 2 years ago. “It is too expensive to go there,” said her. Langar is not too far from Murgab. It is around 250 km only, but the public transport there is very rare and expensive. At present, Murghab-Langar cost 50 Somoni/pax. Gulnara’s salary is only 80 Somoni per month. She hardly manages to feed her family with that money, needless to say to visit her brother.

How about Gulnara’s husband? Beig is a 56 year old man. As 80 percent of the Murghab population, he is unemployed too. At least Beig also used to earn some money for his family. He worked in Russia. “Working ther is very hard. Life condition for people with no money like us is very difficult. And the salary was not that much either.” Beig used to work in Moscow as a cheap labor. But he returned back to Murghab since a year ago. Now the whole family only relies on Gulnara’s shoulders.

Gulnoro and her hardships

“Q’in (hardship)” and “bicchara (poor)” are Gulnara’s favorite words.

“Life here is so poor and difficult,” said her for dozens of times a day. With the 80 Somoni (25 dollars) per month, Gulnara has to feed her husband and her 3 children. “Even a sack of flour cost 70 Somoni already, and it’s not enough for a month.” Rice, used to be Gulnara’s favorite food, has long disappeared from the family’s menu. Rice cost 3.5 Somoni/kg, about a dollar. Everything has to be bought from market, as most people in Murghab doesn’t have land to cultivate agriculture. And together with the rise of oil price, now all products are also expensive. Even potatoes, which Gulnara used to eat for free in her home village in Langer, now have to be paid with 2 Somoni per kilogram. Luckily her elder brother in Langar still sometimes sends her potatoes for their daily need.

Why Gulnara chose to move to Murghab when she had such a paradise-like village in Langar? Her husband is from Murghab. Her husband’s family is all in Murghab. Now it is only Murghab which is her fate of today and tomorrow. “Even if I decided to move to Langar, I wouldn’t have any place there. Of course, life in Langar is much better than here. But now Murghab is our home already.”

Despite of today’s low salary of Gulnara, the family cannot be said completely poor. They have a house. A big one with two rooms. One room for summer days, as it’s big and airy. The other room for cold winter days: smaller and warmer. They have toilet outside the house. It seemed the tradition of the Tajiks, not to put toilet inside the house. The family has a TV, with digital satellite. Gulnara has an old electronic oven to bake bread, and the kitchen’s chimney never stops blushing ashes, to the cold sky of Murghab. Thus said, even Gulnara’s salary is lower than a Jakarta beggar (a beggar in Jakarta may earn 60 dollars per month), she never ashamed of her life. Even if Tajikistan’s national budget is embarrassingly low, no people are allowed to be homeless. The communist days had pushed the lowest class of the society to much higher level, brought all people to almost an equal standard. Other Asian countries with much flourished wealth (Indonesia, India, China, etc) are still troubled by homeless, beggars, street crimes, and so on.

Everybody loves Hadisa

Gulnara has a tragedy, and she might be the reflection of Murgab’s community. She has 2 sons and a daughter. Akim and Alim, 16 and 14 years old respectively, are strong young boys, studying in the local Tajik school happily. But the younger sister, Hadisa, 9 years old, has a brain of a 2 year old child. Saliva never stops flowing out of her mouth. An everyday she needs a book to destroy. When she is happy, she always laughs, showing her incomplete teeth. When she is angry, she screams and kicks the wooden platform with her two legs. The 9 year old girls still cannot open the candy wrapper by herself. She is always curious, and tries to reach any strangers or things that she doesn’t know before. Often she frightens the guests and Gulnara has to push her to the corner. She lives in her own world. She doesn’t posses the worry of tomorrow which Gulnoro, Beig, and other people in Murghab owns. She lives in heaven of her own. After some days living with Hadisa, I started to admire her beauty.

They always keep Hadisa inside the house. Nevertheless, Hadisa wins the love of everybody in her house. When she wants to sleep, she cries out and her father kisses her affectionately until she is quiet. When she wakes up, her mother gives her morning kisses and changes her clothing. Her two brothers also like to tease her the whole day. Hadisa is no more a burden to sorrow but God’s gift to grate. My mute interaction with Hadisa, the poor girl, has thought me a lot of lessons, about grate.

Hadisa is not this house’s unique story. The family next door, just separated by a centimeter thick wooden wall, also has their own version of Hadisa. The Kyrgyz family has a boy which is only two months younger than Hadisa, also retarded. Meterbek, the mentally disabled boy, has little bit more advanced brain development than Hadisa, as he could run himself to the alley and tease the school girls passing. He can speak simple conversation like, “what is your name?”, “how old are you?”, etc only in Kyrgyz language. My interaction with him was mute anyway.

Meterbek, the boy next door

Meterbek and Hadisa are not the only Murghab’s unique stories of shame, which people tend to hide or deny. Later I saw two or three other retarded children in the neighborhood, all from the same range of age: 9 to 11 years old. This makes me think, what happened to Murghab. Was that the war? Was that the poverty? Gulnoro didn’t give me any answers. She might feel unease with the questions. Most other people from Murghab, for example those from NGO, denies that the phenomenon exists in their town. Later I met a doctor from Murghab in Osh (Kyrgyzstan) who confirmed about those retarded children of Murghab and discusses about the possible causes with me. “Maybe, it is still a maybe, during the civil war, when GBAO was blocked by the central government, there was no food in the area.” Retarded children can be caused when the mother has bad health during her pregnancy. It might be also due to lack of health service during the difficult years: no hospital, no immunization, no medicine. Other guy from an NGO proposed that mental retard can be caused by genetic or anemia. But I wondered whether all of Murgab citizens are carrier of retard genetic. For me, the most possible factor is the civil war, which might be direct or indirect cause of this. One may ask, didn’t the Aga Khan provide the food supply to all people in GBAO during the war, up till 10 kg per commodity per person? But if you notice the age of the retarded babies, most of them were born (or developed in mother’s womb) during the peak of the war, when even the Aga Khan was still negotiating his way to Pamir. Whether it was lack of food, lack of health service, or prolonged mental stress, the war (which never physically came here) had left scars that cannot be erased during the lifetime of those babies.

Life in Murghab, just like life in any frustrated areas, imitates the life of those retarded babies. About 70% to 80% of people are unemployed. Even those who has job, like Gulnoro the school teacher and Dudkhoda’s wife – the bread seller, only earn 20-25 dollars per month. Everything has to be brought from the bazaar. Tajikistan was hit badly by the oil price, and by its own currency. I don’t know why such a financially poor country has to have such a big currency (US$ 1 = 3.45 Somoni), which make people tend to round everything to the closest Somoni unit and give up the dirams (1 Somoni = 100 diram). Everything is expensive here, while most people don’t earn even their country’s biggest banknote (100 Somoni, about 30 dollars).

How frustrated and pitiful the bazaar of Murghab. The bread seller only brings 7 to 10 breads to her own little space, and only sells three of them after three hours of waiting. That is 3 Somoni. Young men with nothing to do during the day got drunk after a bottle of vodka, which they brought in share (the money is from unknown reason, but remind you that Murghab is very dangerous after dark!). These men got drunk in the bazaar at the middle of the day, harassing people who did window shopping (in a bazaar without window at all but what you can do besides window shopping when you have no bills at all in your wallet?). Frustration of life brought people back to alcohol virtual fun. Those who still can resist spend their days by just watching the time passes-by: city walk, gossip, or slaughter the time on a chess table.

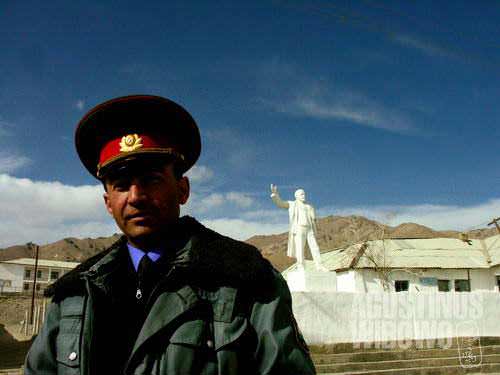

A bored police with Lenin statue

Murghab might have sad picture of today and still remember the glorious past days. The Lenin statue still stands at the town center. It is said as the only Lenin statue remained in whole Tajikistan. Just next to it is a police station. In front of it is KGB office. Behind it is border military station. The little town is heavily militarized, as the president Imamali said, GBAO is the golden gate way to the golden era of Tajikistan. But anyway, there is not much to do here. The policemen were very bored during patrol time and did nothing else but stopping the Kyrgyz girls to be photographed together (by my camera). The border policemen also work as shepherds in the morning to take their animals to the pastureland, when the day is still freezingly cold. But at least they still have something to do, no?

Murgab is a unique town in Tajikistan. It has important role as a frontier. But the population is not Tajik anymore. The proportion of Tajik-Kyrgyz population was about 30%:70% to 20%:80%. Most of the Kyrgyz population don’t speak Tajik and vice versa. The communication between ethnics were delivered in Russian, the language of the past, the language that has traveled thousands kilometers away from its birthplace to unite Central Asian ethnics in these high mountains.

In the sensitive border area, avoid anything military at any cost!

The fact that it is now under the Tajik flag slowly changed the Kyrgyz community here. From the old generation who only know how to say “Tajiki namidonam (I don’t know Tajik)” to the schoolchildren who can talk little bit more advanced Tajik language. The Kyrgyz dominated the bazaar. You can buy easily Kyrgyz kalpak (traditional hat) here rather than the Tajik scull cap. The military and security is heavily dominated by the Tajiks, maybe they still suspect the loyalty of the Kyrgyz nationals, who might be better to be in the neighboring Kyrgyzstan. There are separate schools for the Kyrgyz and Tajik students, which determined the language of education. One day Gulnoro takes me to her class. She teaches every thing, from Tajik language to math. She handles the 4th grade and when I was there they had test. The class was small, only a dozen of students there. It was a very comfortable classroom. Tajikistan, despite of its poverty, still pay heavy attention to the education of their future generation.

I take a look at the text book of ‘Citizenship education’. It was an interestingly good book about Tajikistan political system, the presidency, until explanation of president’s quotes (like ‘water for life – ob baraye hayot’). There are many photos in the book. Akim says he likes that class very much, as he learns a lot about his own country. But when I tested him about the capital cities of the neighboring countries, he didn’t even know the names of the capitals of Moldova, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Latvia, and even the closest neighbor, Kyrgyzstan. He only knows that Moscow is the capital of Russia. Beig, his father, was very upset and ashamed. “I served my military service in Kiev. My children even don’t know where Kiev is!”

The uncertainty and frustration of life was also reflected now in the mind of younger generatins. I asked Olimboy, Gulnoro’s 14 year old boy, “What do you want to be when you grow old?”

He answered, “a driver!”

“A plane’s driver or a bus driver?” I still tried to find explanation to my surprise.

“A bus driver, of course,” Alim was sure.

Tursunboy, a boy from the Kyrgyz neighborhood, was also there, and gave the same answer confidently, “I also want to be a driver!”

Beig seemed very unhappy with his son’s answer. “What is this??? I don’t want to have a child who only wants to be a driver. What life will be? No ideal at all!”

His wife doesn’t think being a driver is a bad thing at all. “What’s wrong to be a driver? In Tajikistan drivers also study in universities!”

Even the dreams are flawed.

In a place where transport is very difficult and it is only people with cars (Alim family doesn’t have car at all) and drive can earn money with full confidence, don’t blame it if the young generation put drivers as their ideal.

Again, I have to copy Gulnoro’s words to conclude life in Murghab. ‘Q’in’ is never overused here. Works are not available, things are expensive. Frustration is reflected by alcohol consumption and empty looks of the retarded children, the steps of the people on the street going to random directions with random motivation. But here I got very precious lesson to learn: being grateful of anything God has already given.

Leave a comment