Vrang – Life in Vrang

Green, peaceful, and lazy … Vrang

Travelling in Tajikistan side of the Wakhan Corridor was as difficult as in Afghanistan side. Public transport was rare, the oil price got higher as the altitude got higher. It was 3.50 Somoni per liter of petrol here. No one was sure when the coming transport would come. And even when it came, it was often full, no space to share. It was indeed luck to be able to travel according to what one has planned. I was patient enough even though I worried about my short visa.

Dr Akhmed was a doctor in Tughoz. I was waiting for transport to Vrang, 5 km away from tughoz, in his hospital. As the main doctor in this village, he earned only 50 Somoni per month. You would go nowhere with that amount of money in Tajikistan. But everybody was optimistic with his life. Working with little income was still better rather than begging on the streets. I have heard beggars in Jakarta could earn at least 60 dollars per month, about 280 Somoni, or 4 times higher than Dr Akhmed’s income.

You need a lot of money and bunch of patience to travel in Tajikistan.

I was packed in a passenger’s coach going to Vrang, cost 3 Somoni for a ride. I arrived in Vrang without knowing where to go. I met a woman on the street who happily told me that she met the Shah of Panjah, Saeed Ismail (known as Shah Ismail), the religious leader of Ismailis who now lived in Afghanistan side of the river. She said that Shah Ismail came to Tajikistan side of the river for several times. She herself went to Afghanistan side during the Civil War of Tajikistan and sheltered in Qala Panjah for 4 months. She was one among hundreds of people who fled to Afghanistan. How about the military and KGB? They understood the hardship of the people and let them to cross the bridge, illegally. It was indeed a difficult situation for everybody. The woman, who was chewing naswer (1 in 100 women did this), offered me to her house as her husband was a history teacher and she was sure her husband could recount more.

But I met another villager of Vrang, of which made me adoring how high level of education in this poor country. He was an unemployed since the war, but he could mention the four main islands of Indonesia: Kalimantan, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and Java. He was surprised when I told him that Indonesia actually had 5 main islands instead of 4. But how many taxi drivers in Jakarta could name 3 main provinces of Tajikistan?

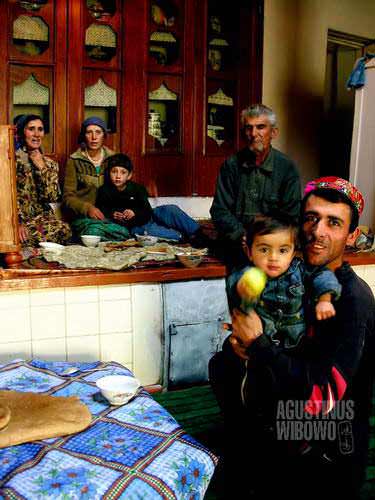

The Khurshed family.

I was invited by Khursed, a young man of 33 years old, who was building a shop next to the main road. He was another unemployed man from the GBAO, despite of his education as a geologist. But he was luckier. His younger brother worked in London for the Aga Khan organization and his sister was the head of the kishlok (village). His house was big and beautiful, and his cute baby, Omed, brought the laughter to the whole family every minute. Khurshed had another younger baby, just 2 weeks old.

I had dinner together with the family. I noticed when having meals, it was always the male family members and the eldest son eating with me together and the women of the family together with other children ate on the platform behind. I wondered whether it was part of Ismaili teachings to segregate sexuality like the Sunnis and Shiites. Later Khurshed explained to me, it was because of special condition of having guests. When there were no guests, the males and females of the family eat together on the same mattress.

“I don’t observe fasting, but I perform namaz (prayers)”, said Khurshed. The Ismailis were much relaxed about observing fasting in the Ramazan fasting month, compared to the other Muslims. The Ismaili’s prayer was also different from Sunnis and Shiites. The position only included sitting position, no standing at all. It also included a motion of blessing, in Indonesian we called it as ‘sembah’, to right and left side, which means ‘imam didar’, respects to the Imams. Khurshed said as they didn’t have concrete jemaatkhana (prayers’ hall), the mass Friday prayers were done in a follower’s house, and ever week there was turn in whose house the prayers would be performed. Jemaatkhana, which mushroomed in Ismaili regions in Northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, was actually enforced by the Highness Aga Khan, and at that time Tajikistan was already under the Soviet rule, where there was huge repression to religious activities. This is why no jemaatkhana existed in ex-Soviet Ismaili regions jemaatkhana didn’t exist (yet).

How the Ismailis split from the Shiites? The 6th Imam had two sons, the Shiite followed the one and the Ismailis followed the other one. The line of Imams of the Shiites stopped after the 11th Imam as this Imam didn’t have son, which was important to continue the blood line of the Prophet. The Shiites were now still waiting for the coming of the 12th Imam, whom they referred as Imam Mahdi. The Ismailis continued the line until now and Aga Khan was their 49th Imam. Both sects regarded that themselves followed the most correct line. In fact, many of the Sunnis and Shiites in Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan regarded the Ismailis are not Muslims.

It is said that 95% people here are unemployed. But how you define unemployment?

The person who brought Ismailism to Central Asia was Nassir Khusrau in the 12th century. At this moment, the main followers of Ismailism in Central Asia included the Pamiri Tajik community in the GBAO of Tajikistan, Hunza and Gojal (Pakistan), Wakhan Corridor and Pul-e-Khumri (Afghanistan), Tashkurgan (China), and some other pockets in India, Iran, and Afghanistan. Ismailis are known for their moderate thinking, high education, and high social role, especially in Pakistan and India. The sect doesn’t have mosque (masjid), and prayers were done mostly as private matters. There was jemaat khana (prayers hall) for religious purposes such as mass prayers or wedding ceremony (nikoh). The religious leaders for Ismaili communities are khalifa and muki. The khalifa dealt more with social problems while mukis with religious problems, like conducting prayers and solving religious questions in the jemaatkhana. But the Ismaili community in Tajikistan, not only missing the jamaatkhana, but they also didn’t have muki. The duties of the muki, for example the nikoh (wedding) legitimating, were done by the khalifa instead.

Being a minority during the Civil War had brought much suffering to the Ismaili Community in Tajikistan. The isolation of the central government had left many people now unemployed. People with high education worked and earned much less than their qualification. Just like Khurshed and most other people in Vrang. People said that unemployment rate in Vrang once reached 95%, but ireally depended on how you define ‘unemployment’. If you regarded people with no formal work and spend their most time in their own garden and field or herding the animals, or car owners who spend their days in the village road to collect passengers and depart once in a week, as unemployed, then it was indeed the fact that almost all of people in Vrang were unemployed. But it didn’t mean that they had nothing to eat as they had some assets.

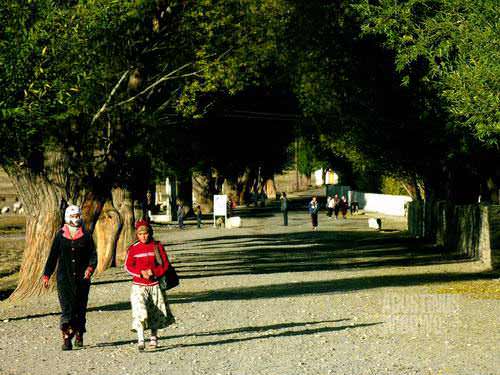

The village of Vrang, in this cold season, really seemed as village where almost nobody had work and spent time by hanging around on the street. The bazaar was sleepy, and there were only 4 kiosks along the 2 km long main road of the village. There was no beggar here as it was considered a big shame. Somehow the communist years had brought everybody grueling on an almost equal line.

Election time, things might get sensitive. My passport, visa, and permit had been “registered” for dozens of times by the police, militsiya, soldiers, agents…

Just because of taking photos of election books, I was suspected as a spy! I was brought to this village office for interogation, but luckily the head of the village is Khurshed’s sister.

People also didn’t have much expectation with the coming election. There was an audience hall in the village which was zipped to be a voting point. There would be 540 voters in the village and 7 people working in the village election committee. Dushanbe provided some books about information of the election, but even one of the committee members told me that the books meant nothing to him. I wanted to get a copy of a book titled ‘100 questions and answers about Tajikistan presidential election’, but the head of the village couldn’t make decision whether to give me the booklet or not. She initially suspected me as a spy, but because I stayed in her brother Khurshed’s house, she believed that I was genuine. She made several telephone calls as far as to Khorog to ask for directions from her leaders. The final answer was bebakshid—sorry.

About the history, Vrang also had curious pre-Islamic relics like the Zoroastrianism fire worshiping platforms (known locally as Kafir Qala – fort of the infidels) and Buddhist caves on the cliff. The village itself was quite big and widespread, facing the village of Izmut on the Afghan side of the river. The road was wide and asphalted, but it was indeed empty and sleepy.

The golden autumn finally arrives in Vrang

I just stayed in Khurshed’s house for a night, but I already felt I was part of the family. When I was lingering the village, Khurshed’s mother called my name and asked me to go to home for lunch. Actually there was nowhere else in the village selling food and meals only can be had in private houses. Even when I got to leave after waiting for public transport the whole day, Khurshed’s mother insisted me to take some bread for me to eat on road. Even life was difficult that they didn’t have much to share, but there was always the spirit of sharing anything could be shared.

The hospitality of people in Wakhan made me embarrassed of myself.

Leave a comment