Khorog – The Journey to GBAO

One of the two brothers, fellow passengers on the journey to Khorog, GBAO, Tajikistan

GBAO, the Gorno Badakhshanskaya Avtonomnaya Oblast (Gorno Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast) is my main reason to come to Tajikistan. It is dominated by the minority Ismaili Badakhshani Tajiks and Sunni Kyrgyz. It has majestic mountain architectures. But the main reason I want to go to this restricted area was its history. The province was supporting rebel side in the civil war of Tajikistan. The province suffered a lot from the blockade of the central government.

Going to Tajikistan is already something strange for my Indonesian friends in Kabul. “Why going to Tajikistan? It is a poor country.” Going to GBAO is another thing to be objected by my Tajik friends in Dushanbe. “Why going to GBAO? It is so far and poor…” Even the Tajik diplomat in Kabul raised his eyebrows when my embassy staff insisted to get a Tajik visa together with GBAO permit. “Is he really a tourist???” For the ‘GBAO’ four letters to be added on my visa I had to pay a painful 100 dollar fee. It is a bureaucratic country, and my embassy told me to follow the rules, as for this visa I was sponsored by the Indonesian embassy. No playing illegal entry this time, like what I did in Tibet.

After finished all of the bureaucracy honky ponky in the capital, I immediately took the transport to Khorog, the provincial capital of GBAO. The 560 km distance has to be covered in 20ish hours and cost 100 Somoni (30 dollars) a seat in a minibus. I was dragged by two boys saying that they had their own car and just needed one passenger to depart. They quoted the normal price so I agreed immediately.

The two boys were brothers. They were going back to their village near Khorog together with another two brothers, one sisters and a mother. They had an enormous number of luggage with them, looked like more trading goods rather than souvenirs. The small jeep was fully packed by the luggage, and the whole family was stuffed inside the tiny jeep, and still there were two seats left, which then a female passenger and I took.

The journey was a happy journey as all of the passengers in our car get acquainted very fast. Bakhtiyor, one of the brothers drove the car. None of the people in the car was fasting. I thought that it was because all of us were travelling long distance. But Bakhtiyor said that he fasted 9 days in the holy month, that is 3 day at the beginning, 3day in the middle, and 3day at the end of Ramazan. “My mother fasts, my wife fasts, my child fasts, so it’s not necessary for me to fast. There are enough people in my family who fast. If I also fast who will work to earn money?” Later on I learnt that these Ismaili sect followers from Khorog believed that 3 day fasting in Ramazan was sufficient. And yes, most people in Khorog don’t fast during Ramazan. It was no relation of being mosafer (traveler) or not. [Muslims are exempted to fast when they travel]

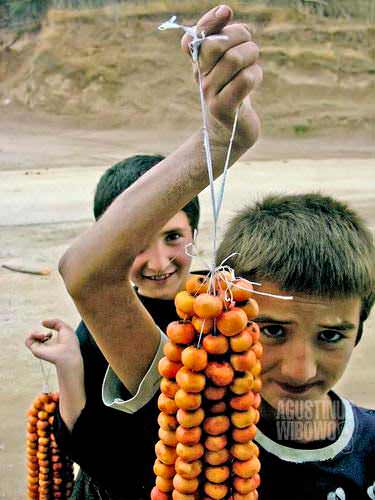

Children offering mountain fruits to the vehicles

Tajikistan is a poor country with rampant corruption. In the first hour leaving Dushanbe, we were stopped five times by the police. Every time, Bakhtiyor had to get off the card with the ‘car passport’ and his mother slipped some 1 Somoni notes in it. No matter how complete the document is, it’s customary to give money to the police. The first asked 3 Somoni, the second 10 Somoni, the next 4 Somoni, 2 Somoni, and 5 Somoni. The dirams (1 Somoni = 100 dirams) don’t work for the police. It was indeed expensive ‘pocket money’ for the police. A police just can stand on the road, stopping 100 cars per day and become the richest man in the neighbourhood.

The month of Ramazan in this secular state doesn’t help much. My money was stolen from my bag in my expensive hotel room, during Ramazan. The other occasion, that made me so much impressed by the Tajik police, when I was taking pictures of Ismail Somoni statue in central Dushanbe, there was a police man who tried to extort money. “You know the month of Ramaza? It is a holy month. It’s mah-e-sharif. So please do goodness,” said him. The ‘goodness’ he wanted was 10 Somoni banknote. In respond I acted poor and told him how my money was stolen. He reduced his requirement to be 5 Somoni. I left him away and he still to emphasize the meaning of Ramazan, to give donation to poor (he didn’t look as a poor at all). The second day I visited the same statue, and the same police asked the same donation, with the very same reason, Ramazan as holy month.

As a foreigner doing nothing wrong, I always can choose not to give. But seeing Bakhtiyor paying the police no matter how complete his document was, made me really wonder how the locals being so much suppressed by the so-called ‘community guardians’. They have their helplessness, and the dirty bureaucratic system has always its own way to lubricate its wheels. Just like a poor tourist who moaned about how expensive the paperwork in Tajikistan cost, from expensive visa, permit, declaration, this registration and that registration, and all need dollars. Everything goes to money. In Indonesian we say, ‘ujung-ujungnya duit’.

Rather than being frustrated by dirty bureaucracy and greedy officers of Tajikistan, I preferred to enjoy the beauty of this country. The road was very beautiful, as Tajikistan is full of towering mountains. 93% of this country’s land Is high mountains and it is dominated by the world’s second highest mountain range, the Pamir, roof of the world. Tajikistan scenery is unbelievably beautiful.

At lunch we stopped in a chaikhana. Not much choice of food during Ramazan and many restaurants are closed. But it is still easy to find something to eat. The women passengers went inside the room, and we, the males, were outside. I wondered whether it had something to do with the religion, just like in Afghanistan. Bakhtiyor laughed, “No, no at all. The women sat inside because it is warmer there.” About the Afghans, the people next to the river visible from GBAO, Bakhtiyor showed disgust. “They are animals. The wheat also smells donkeys and horses. There is no car there, so the rice and wheat is transported by animals. The rice has strong donkey’s smell so the people also changed to be donkeys.” It was a rude commentary. Bakhtiyor showed his strong dislike toward the fundamentalists.

I sat next to the female passenger, Samsiah. She sometimes laid her head on my shoulder and we joked freely. After 6 months in Pakistan and 3 months in Afghanistan, I felt little awkward to communicate with women. Samsiah also enjoyed sharing my MP3 player to listen to some music. We sang together along the way, from Iranian, Afghan, Indian, until Russian music. As a small country but sharing ancient history with the great Persian civilization, music from Iran and Afghanistan is also popular in Tajikistan. Samsiah, and even the big grandmother, could sing some hits of DJ Arash, not to mention those songs of Fayad Darya of Afghanistan. I was surprised that she even could sing ‘kuch kuch hota hai’ in Indian version. How Indian movies gained popularity in Tajikistanis still a mistery for me.

When we sang Russian songs, I naughtily changed the lyrics of a pop song in 2004, ‘Znayu’. The original one is ‘znayu, skora tebya pateryayu (I know, I will lose you soon)’. And I said, ‘Znayu, skora sumka pateryayu, maya i tvaya …( I know, I will lose luggage soon, mine and yours…)’. Everybody laughed.

Not even 60 seconds passed, suddenly…. BRAKK!!!, the whole luggage from TV sets, DVD players, and my backpack, flew away from the top of the jeep to the road. It was just started to rain, so we rushed to rescue all of our ‘sumka’ and stuffed everything inside the car. Now sitting in the fully packed jeep was much more difficult. And I am worrying whether now I possessed a supernatural ability to forecast bad luck…

Isolated mountains, … but with asphalt road connection. Thanks to the Soviets.

The M-41 highway had been completely asphalted but many sections of the road are damaged. I couldn’t help myself to admire the Soviet union, ex-superpower which could build smooth roads until its troublesome frontiers like Tajikistan. Soviet Union had Tajikistan and Indonesia has Papua. Tajikistan was a frontier with civil unrest and Islamization threat. Papua is a frontier with separatist threat. Soviet built road connecting the villages of Tajikistan, supplied it with complex web of electricity network through the impassable mountains from the roof of the world. While in Papua, flight often becomes the only choice of transport and Korowai people living on the trees in the jungle still don’t bother to buy TV and DVD players. Indonesia is not Soviet Union anyway, so indeed there is no point of comparing.

Now, the highway which was built by the Soviet Union turned to be dirt road in many sections. The poor Tajikistan fell to civil war and road maintenance was not on priority in the warring country. It is now the Chinese engineers and workers who flood the country to offer road maintenance aid programs.

Almost 10 p.m. we passed the high pass of Khaburabot, which was covered by snow already. The weather in Tajikistan was not good at all these days with heavy clouds and whole day rains. On tops of mountains, it became snow. We were extremely lucky that we succeeded passing the slippery pass as it was midnight and it was not nice to get out and push the car under freezing temperature like this.

Kalaikum, the gateway to GBAO, has important checkpoint to control the traffic of people and vehicles. Everybody has to show passport. In Tajikistan, passports act as ID cards. Thus, there are two kinds of passports: the local and international one. The young soldiers, I think at most 20 years old, were so happy scrutinizing the passengers’ passports. One of the brothers in our car, a mute boy, doesn’t posses passport. The soldiers also started to ask about my registration. I didn’t put any somoni notes in my passport. Rather than confronting the soldiers, I started conversation with them.

“Do you enjoy your work?”

“Enjoy? What enjoy? This is mountains, you see, only mountains! I miss my wife! There is nothing here!” said a 18 year old soldier from Dushanbe.

Being posted in the middle of nowhere like this and still had to patrol in freezing midnights was of course not among the things people of Dushanbe wanted to do. The other soldiers kept asking about the passport of the mute boy. Obviously they were seeking for bribes. Suddenly a boring soldier asked me the time, as I was the only one with watch. It was 11:40.

“Yawazdah o chihl,” I said. I didn’t know what was wrong with my Persian pronunciation, all of the soldiers laughed to death and let our car pass. They forgot about the missing identity of one of the passengers. We didn’t pay any dirams to the soldiers. Now I found that being jovial can be a solution to escape corrupt officers.

After passing Kalaikum, the road quality miraculously turned to be very good. I wondered that GBAO didn’t experience the civil war at all during the difficult times of the country. The province was merely blocked by the central government but fighting didn’t really come here.

Khorog, the mountainous capital of the mountainous GBAO

At 6 a.m. it was a cold morning, we arrived in Khorog after 18 hour journey. I didn’t see much scenery along the way, as the weather was bad and Bakhtiyor drove through the whole night. He relied on naswar (nas) to keep him awake and now his breath smelled very heavy.

So, welcome to GBAO, the land on the roof of the world.

Leave a comment