Garmao – The Journey to Jam

Travellers (musafirs) sleeping on the floor of restaurant along the central route of Afghanistan. The restaurants also serve as hotel for passengers. Along the isolated Central Route, the most common way of travelling is by hitchhiking a truck, like these.

Same quote as a previous post from Iran, same story to be happened (again).

After waiting for two days for transport heading east from Chisht, at last I found these two trucks. They were repairing the broken trucks when I came there out of the Chisht bazaar together with Abdurrahman, a boy from the village.

Kalendar, one of the truck drivers, agreed to take me. But I had to wait 2 more hours until they finished repairing the broken truck. The night before, I had talked with another truck driver in the Iqbal restaurant to take me to Kamenj. The driver quoted astronomical price of 500 Af for the ride (normal price was 100 Af by truck). I bargained it down until 150 Af. He agreed and told me to be prepared at 8 a.m. But this was a Persian taarof culture, refusing but avoiding saying ‘no’. The truck left as early as 4 a.m. and I was still sleeping. People could be very untrustworthy here.

Ta’arof culture was also in Afghanistan, especially in the western part of the country populated by the Farsiwan ethnic, where the Persian influence was strong. Another driver, instead of saying, “sorry, I don’t go that direction,” quoted an impossible price of 800 Af for the 100 km distance.

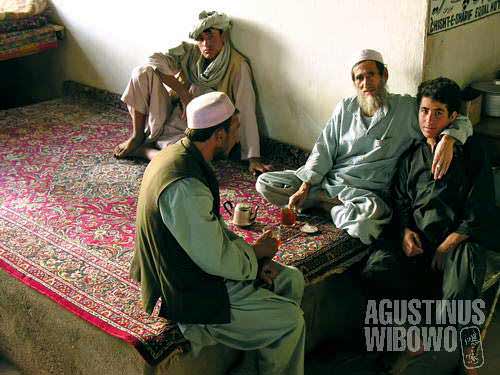

Atmosphere in a teahouse in Herat province. Teahouse is not only a place for taking meal and drinking tea, but also a socializing place for the villagers to exchange gossips, as well as place for travelers to break their journeys.

But Kalendar, fortunately, was not Herati with all of these difficult-to-trust ta’arof (what we call as takallouf in Urdu or basa-basi in Indonesian) sweet words. He was a Tajik. Another driver was a guy whom they called as ‘Misteri‘, literally means ‘mechanic’, also a Tajik man. Together in the truck were two assistant boys, Qurban, an 18 year old Hazara boy, and Rafiq, a Pashtun. Being from different ethnics and religious sects was not a matter for them, even though sometime the Sunni Tajiks and Pashtun ridiculed Qurban of performing zanjirzani, the Shia tradition of self-torturing with knife whipping during the mourning month of Muharram.

“We are not crazy. Only he is crazy,” said Rafiq pointing to Qurban. The Hazara boy just smiled.

Traveling with broken old Kamaz truck was incredibly slow. To cover the 40 km distance to Der-e-Takht, the last village of the Herat province, we needed 2.5 hours. We had lunch there and the guys took the chance to pour cold water from the river to the boiling truck machine. Crossing the bridge of Der-e-Takht, then welcome to the poorest province of Afghanistan, the isolated Ghor province. The hills were dry and barren, as failed harvests had been the fashion for years. The roads in the whole province were dusty unpaved narrow paths, transport was expensive and rare. Locals had to rely on hitchhiking on trucks or the fully crowded Falan coaches for traveling.

Misteri was driving the car. Qurban was sleeping on the back seat. Rafiq was burning and smoking opium. I couldn’t stand the smell of opium, and I fell asleep. At this time, without my acknowledgement, I experienced a near-to-death experience.

Suddenly I was awaken when Rafiq pulled out my shawl of my neck, and threw it out the window. Once the shawl reached the dry bush out there, it burnt the whole plant around. I was stupefied by what happened, and only could question, “chera…? (but, why…?)” . Had the shawl hung around my neck for a few more seconds, it would have been me, instead of the bush, which was burnt.

This incident happened like this. Rafiq was burning and smoking opium. I was sleeping between him and the door. Eventually he threw the matches out the window. One piece of the matches stuck on my shawl, instead of went outside. Qurban, who was sleeping on the back seat, accidentally awaken up. He saw ash from my body, but he thought he was just dreaming. He looked at the scenery outside, then he looked back at me. The ash turned to be fire, as it had reached my vest. He screamed, “FIRE!!!!”

Rafiq realized what happened, and in reflect, pulled out the burning shawl from my neck and threw it out.

Now I was convinced, opium smoker could be dangerous at any time.

The truck traveled slowly, and when we were about 2 hour distance from Garmao, the Kamaz completely stuck. It was broken. And we blocked the narrow road totally. Kalendar and Misteri, the two mechanics, were not panicked at a ll. Soon it became traffic jam of several trucks and Falan coaches with angered drivers. The damage of our truck was serious, as the accumulators didn’t work at all and the machine could only produce black poisonous gas. It would take hours for repair.

Some of the boys from other truck, who knew exactly that they wouldn’t go anywhere for the next few hours due to the traffic jam, caused by our broken truck, started to wash the beef with river water, peeling and slicing the onions. They were ready for cooking.

But the drivers from other cars were not that relaxed. They were angered, and urged Kalender and Misteri to repair the truck as soon as possible. No aid was given though. After about an hour, the traffic jam became very long, and the other drivers were panicked as the day became dark very soon. They successfully found another Kamaz from the opposite direction to pull the Misteri’s broken truck out of the way.

The traffic jam dissolved. Only six of us left with a broken truck. Misteri then told me to walk to the nearest village as it would be impossible for them to continue. The drivers and assistants would stay on spot, trying their best to repair the Kamaz. I paid my ride, 100 Af, and left.

Now I felt helpless. I walked alone through the dusty road, and it became dark already. I didn’t know where would be the next village. It was very cold at night in Afghan mountains. A car passed. Another Falan coach passed. And a motorcycle passed. None stopped for me.

I kept walking. Suddenly I saw the car and Falan coach stopped next to the river down hill. I rushed my way there. It was night prayer’s time, and the religious Afghans wont let themselves to miss any second in performing the prayers. Thus it was the chance for me to catch the Falan coach and talked to the driver.

I talked to him in helpless tone, emphasizing that I was stranger in the middle of nowhere. The driver agreed to take me until Garmao, where they would stay overnight. The coach was fully packed with 18 passengers (included me) from Herat to Chekhcheran. It was 2 day journey, stopping overnight on the mid-way, the village of Garmao. It cost 800 Af for the whole ride.

The passengers were excited when I came into the car. They were all interviewing me, wondering how could I be there. In turn, I was so dizzy in the bumpy, crowded, hot, coach with empty stomach. It was a 1.5 hour journey to Garmao and I felt relieved when I reached the dark village.

The samovar of Garmao was very basic. The floor was dusty and the carpet was dirty. The food was incredibly simple but very expensive. This restaurant was very busy that night, as there were three Falan coaches and some trucks stopping here. The hall was packed and I ate outside with some other passengers, curious about my journey.

Everything was nice at that night. The passengers were friendly, and they weren’t really into religious discussion at all. The young, fat Falan coach driver refused my payment. “Baksheesh,” he said, meaning, ‘I do a good thing for you.’

It was already 10, and people were preparing to sleep. The restaurant hall was really packed. People slept on the floor in rows and lines, one close to the others. When I took off my jacket, I realized one thing: my harddisk was not in my pocket anymore.

The hard disk was a portable hard disk of 100 GB size, which can copy the files directly from the camera’s memory card. Thus, all of the photos of my journey, starting from Tibet to Afghanistan, were saved in the hard disk. Losing it means losing all of the records of the journey. Something that I couldn’t afford at all.

I was really panicked. The passengers saw my anxiety and asked what had been lost. But how could I explain ‘portable hard disk’ to the villagers of Afghanistan, where electricity was still rare and digital life had not even to appear yet?

“Durbin… durbin…” I said helplessly. Durbin literally means ‘far-look’, is the Farsi word for ‘telescope’, but is used by the Iranians to say ‘camera’.

I rushed outside, back to the coach. I searched the back seat where I sat before, with a dim torch given by the driver. Nothing was there. I ran away to the riverside where I performed toilet business. Nothing was there also. I was very, very panicked.

The friendly restaurant owner announced the lost to all passengers sleeping in the hall, requesting anybody who knew the location of my ‘durbin’ to inform him soon, as the ‘durbin’ was so important to the ‘khareji’ (foreigner). Without me knowing, he started to search the luggage of the passengers one by one. A security check specially for my ‘durbin’.

‘Peida misha… peida misha,” said a fellow passenger assured me. This time I couldn’t think anything else. The driver went back to the car and searched the seats thoroughly. After 10 minutes of searching, he came out.

He had my harddisk in his hands.

I couldn’t express how I felt grateful to him, and to God, to give me one more chance out of my carelessness. The coach was very crowded and packed, and I found it was possible that the hard disk fell down from my pocket when I was sitting there (the hotel owner told me another version of the story: the passenger next to me picked it from my pocket and hid it in the car). When I came back to the hall, the atmosphere turned to be a joy. They were still searching the luggages of each passenger when the driver came back and announced, “peida shod … (it was found)”. The crowd was excited and they came to hug me, to congratulate me. I was really touched by the hospitality and honesty in this poor village.

For my safety, the driver told me not to sleep in the hall, but inside the coach. I accepted. It was very cold inside the car at night. And I was not alone. The Afghan couple (luckily consisted of a man and a woman) who slept also inside the car was really active during the sleep. The car vibrated most of the time during their movement.

I didn’t care. I was still overwhelmed by my luck.

Leave a comment