Krat – The Wakhi People of Krat

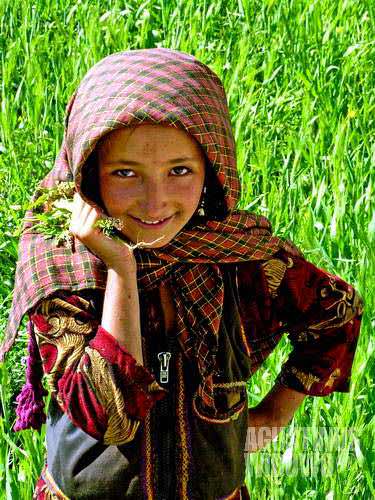

“Zdravstvui tovarech” – a villager from Krat

Freedom is what the Wakhi people are longing for.

I never expected my visit to Chapursan, the Wakhi Tajik valley in northern Pakistan, brought me to learn deeper about the life of the same ethnic in Afghanistan side of the valley. In Chapursan, 7 months ago, I stayed in house of Noorkhan, a Wakhi Tajiki from Kil village, where sun doesn’t come at all in winter for 3 months. Who expected, deep in restricted area of Wakhan Corridor, I met friends and relatives of Noorkhan.

Faizal-u-Rahman, 29 years old, is a cousin of Alam Jan Dario, a famous man from Zod Khon village in Chapursan, who pioneered tourism in the valley. I met Faizal in in Khandud. He was offering me a hitch on tractor to the village of Krat in Wakhan Valley of Afghanistan. He, together with other people from Chapursan are working for an American NGO, Central Asian Institute, and this moment they are building a school in the village. Chapursan is an area dominated by Wakhi Tajik people, same as in Wakhan Valley, and the Wakhi people follow Ismaili sect of Islam. Only Ismaili Pakistanis were hired by the NGO to work in this Ismaili area, and most of them are from Chapursan.

I walked from Ghoz Khan to Krat. I started at 5 in the morning and arrived at 3 afternoon. There were some big streams to cross before the bridge in Soust. I was offered by Noor Ali, a man riding a horse to Qala-e-Panjah, for a hitch ride until the bridge. This is a Wakhi hospitality. Some streams were so difficult to cross on foot as the water was strong as and as deep as a man’s waist. I was so thankful for the horse ride. Noor Ali, the horseman, said, “baksheesh.” In Pakistan or India, baksheesh means asking for money, but here it’s merely a reply of thank you. Noor Ali is working in Qala Panjah, and the horse ride from Ghoz Khan takes him two hours to reach Panjah.

Travelling in Wakhan valley is difficult, as transport service is not existent. People would be very lucky if they can hitchhike to shorten up their journey. I was not that lucky though. That day, in my 8 hour journey, I saw not even a single vehicle going to my direction. The scenery was stunning, nevertheless. The high snow peak of Baba Tangi after 6 hours walking was simply impressive. When I arrived in Krat, after about 40 km walking distance, I was not even able to move any of my legs. I ate almost nothing since the morning. I was relieved I arrived in Krat and there was hospitality there to save my life.

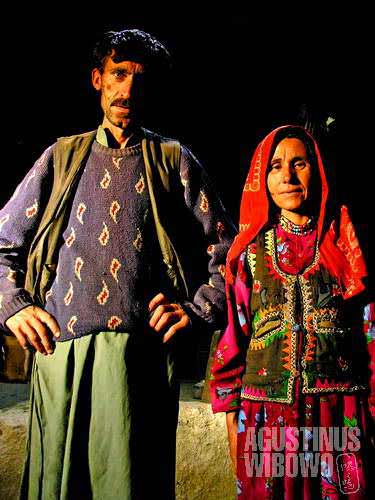

His name is Bakhtali, 35 years old. People call him Moalem, means teacher, as he works as a teacher in school tents near the village. Faizal Rahman took me to Bakhtali’s house in my first moment in the village. Bakhtali said he liked guests very much.

“I am a communist. Communist is good,” said him, while proudly showing his communist party member cards and some communist cadet awards during the regime of Najibullah. All of the cards were written in Pashto, not Dari. His old photos look very young and handsome. Now his face is more rough, thin, dark, old – emphasized by the thick moustache.

His wife served us milk tea. As in Chapursan, the tea is mixed with salt. I dipped my nan (bread) to the tea while listening to Bakhtali’s story. His wife joined us. This is Ismaili area, where there is no restriction towards women.

In other places of Afghanistan, if you are male, don’t dream such an intimate connection with the local women

“Tajikistan is good, there is freedom there,” said Bakhtali, “it’s the mordernization of the Soviet (Sheravi).” Bakhtali’s idols are Engels, Lenin, Marx, and Stalin. “When Gorbachev led Soviet, he only talked about democratic, democratic…, then everything became kharab (broken).” After the Gorbachev’s perestroika programs, the Soviet republics gained independence and communism collapsed. Bakhtali likes communism, but he doesn’t like China. “China is not real communist. Vietnam is better.” For him, China is a capitalist, following a system where only the rich got benefits and the poor are suffering. There is one sure reason why Bakhtali liked communism very much.

It’s the freedom.

Women didn’t need to wear burqa, girls might go to school, and education was high. It is the freedom which was offered by communism, which attracted the symphaty of the people in the valley. And Bakhtali is not alone here.

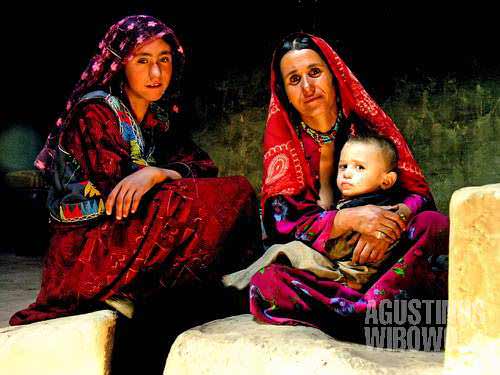

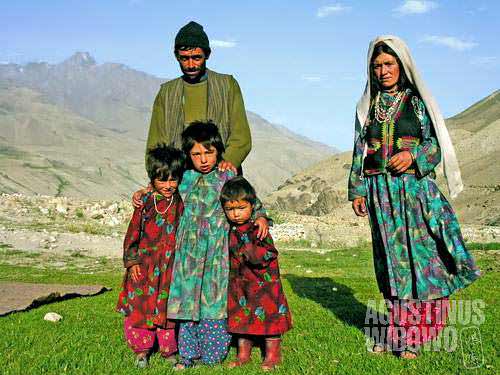

Bakhtali is poor. He has four children. The biggest two daughters are Sultan Atab and Sefida. Their mother didn’t know the daughters’ ages exactly, she guessed Sultan was 16 and Safida 10. It’s time for Sultan’s marriage already. Bakhtali said Sultan was astill 15. But the groom for Sultan was decided already, a distant relative of her mother in another village. Bakhtali’s two boys are Dela (4 years) and Shir Hussain (2 years). There is a certain turn between Sultan, Safida, and the mother to carry Shir Hussain on their backs, make him quiet and happy. Bakhtali has to provide life to these for children and wife. Nan, milk tea and rice have to be made from the dark kitchen everyday. It’s not easy. Bakhtali only earns 50 dollars per month and since 4 months the money has not come yet.

“The government of Afghanistan is very bad,” said Bakhtali in Farsi. Life is more difficult, as Bakhtali has a very bad habit. I regretted to know, that he is an opium addict.

One afternoon, after walking around the village, I returned to Bakhtali’s house. In the room I saw an old man was busy of burning something. It was opium. Bakhtali’s wife gave me signal to take photos of that man, but the old man got very aggressive. “NA KO! (Don’t do it!)” he screamed.

Bakhtali came. I know that day was his addicted day. Since the morning he was talking about how difficult his life was. He stopped talking about his communism ideas; instead he talked about the drug addiction, about his disease, and about his desperate of money. Drugs change people. Bakhtali is an example.

I examined how the opium to be consumed. First the old man crushed the stuff to powder. It’s then to be mixed with water and crushed again until it become really smooth. Then the smooth powder is put at the end of a pipe with shape resembles a question mark, and burnt on small fire. At the other side of the pipe, the man smoked and the drugs threw him to heaven.

“What is that?” I asked Bakhtali.

“Taryaq (opium),” answered him, “but believe me, I am not going to smoke it. It’s bad.”

Nevertheless Bakhtali sat next to the old man, and smoked the opium together. He forgot what he just had said some few seconds before. His wife, his babies, just watched the activity, unable of doing anything. Or for them this ceremony has been common scene.

Taryaq is not cheap. Bakhtali told me it cost 100 Afs from a saudagar (merchant) from Faizabad, while showing me the size with his fingers, about 1 cm size. Later I learnt 1 gram of taryaq from Baharaq cost 500 Af. It’s far beyond Bakhtali’s financial power.

I know addicted man can be dangerous when they are in hunger of drugs. And today was Bakhtali’s “not well” day. It was the reason for me to decide not to stay any longer than a night in his house. When I tried to leave, Bakhtali implied to me to give him some money.

“Yesterday, my little boy, maida (“the little one”) said to me, ‘father, please ask the foreigner to help me….’”

I looked at Dela, deep at his little eyes, “What help you want from me?”

Dela is only 3 or 4 years old and I never heard him speaking. Bakhtali represented his son to answer, “Anything!”

I said I would think about what help would be helpful for such a small boy, maybe notebook and pencil.

Bakhtali felt helpless, “I am a teacher. Books and pencils are abundant. Paisa! Paisa! (money! Money!).

Dela just looked at us. I doubted he understood the conversation. When I left the house, Bakhtali followed me and kept talking about their hospitality, about how difficult it would be if I was in Sunni area, about other Japanese who gave him money.

He is in hallucination.

I was thinking before of giving something to the family. I know their life was difficult, but they still shared their rice with me. I also asked Baktali to seek doctor in Ishkashim to stop his addiction, for his children’s future, and I don’t want to push him deeper into this evil. Giving the money to him directly is dangerous. I was thinking of giving some money through Faizal to let him to buy some rice for Bakhtali. But this would leak Bakthali’s secret as opium addict in the village and the shame would be a burden for the whole family.

Drug addiction is something notorious to the Wakhan people. It was a more severe situation five years ago. The development from the Ismaili leaders brought reduction to number of addicts. The opium is not grown in the valley. It is brought from lower areas like Baharaq and Jurm. People of Baharaq only grow but not consume. People of Wakhan only consume but not grow.

Before leaving Bakhtali’s family, let me tell you how I was impressed by them. The hospitality was my first impression of the family. The wife always joined our conversation, smiled, and posed for photos. “I am a communist, not a fundamentalist,” said Bakhtali. Only Bakhtali speaks Farsi, the others in the family speak Wakhi, a Farsi dialect, the language of the Wakhi Tajik people. The wife, as other women in the village, also was not hesitant to breastfeed her baby in front of guests (in the village/kishlok, some women also breastfeed the babies on the village main road).

“Ismailis are people of freedom,” said Bakhtali, “we don’t have purdah and cadar” Only when the women go to cities further than Iskhashim, they have to wear burqa. It’s pressure from the Sunni people. It’s not the tradition of the Ismailis. Bakhtali doesn’t have burqa in his house. He has to borrow from the neighborhood when his wife was going to the bazaar. He even couldn’t not pronounce the word ‘burqa’ properly. “What is that? Bukra? Burka?” The local word for ‘burqa’ is ‘cadri’.

Bakhtali is a man. For him burqa is bad. For Ismaili women, it’s even worse. Bibi Sarfenaz is a respected woman in the valley. She works for Aga Khan foundation, and is busy traversing the valley for her works. She spent 6 years of training from Aga Khan Organization in Ismaili areas in northern Pakistan. She expressed her impression of the development there, of the high education of the women there. Bibi Sarfenaz is 35, but is still strong to walk along the Wakhan Corridor and Wakhan Valley when necessary. Her office has a car, but not always available for her to use. That day she was in Krat for a survey.

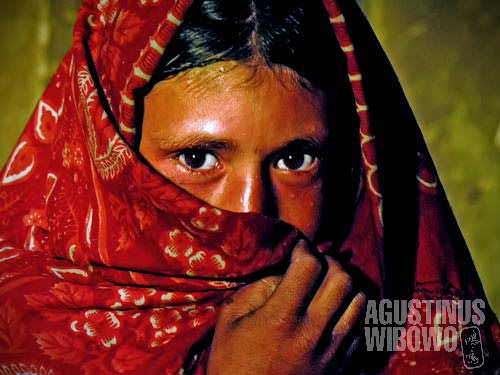

“We like freedom. Ismailis are lovers of freedom. There should be freedom for women, as women are equal to men,” said Bibi Sarfenaz enthusiastically. While the Sunni women are usually not allowed to go to the mosques, the Ismaili women go to their jemaatkhana (prayer hall) together with the men, 3 times of prayers a day (Sunnis pray 5 times a day). “We don’t have purdah, cadar. But when we go to cities, we have to, we have to wear the burqa, because there are many Sunnis there.” Bibi Sarfenaz hates burqa as it is a symbol of women oppression. She has burqa in the car, as it’s necessary to wear for long distance travel, otherwise, she would be considered as ‘halal meat’. She agreed to show me how the burqa to be worn, how a face of a woman to be fully covered by anonymous blanket. Just at the second when the white textile fully covered her face, just at the second she became anonymous, I felt the shock. Once again, she said, “Burqa is not our tradition… we are just forced to…”

The longing of freedom also made Bibi Sarfenaz like Tajikistan. The women there also work and don’t wear burka. “Do you like communists?” I asked her. “Communists are not bad,” answered her. Tajikistan, the brothers and sisters of the Wakhi Tajiks who has been Russified, is now an ideal for the people in this undeveloped Afghan side of the river.

“Zdravstvui tovarech,” greeted a villager to men when I was strolling in the village. Tovarech is Russian term for ‘comrade’, brother of the same idea. It is a word which was commonly used in the heydays of communism. Here, in isolated Wakhan valley, the ideals of freedom, ideas of equality, the ideas which were offered by the communists, are still alive. And it’s Tajikistan, the country just across the river, a country which once lived under Communism red spirit, which always become the dreams of how life should be.

Tajikistan might be only ideas, as now these people life under the flag of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, where they have to follow the culture and idea of the majority. Ismailism is always minority, and as in Pakistan and Iran, they often seen as non-Muslims by the majority Sunnis and Shiites. They follow their spiritual leader, the Aga Khan, whom they believe has the direct leadership line since the Prophet. “For us, it’s insianiat (humanity) which is the most important. Any insane (human) from any religions are the same. Religion is in heart, not on the clothes nor on tongue,” said Bibi Sarfenaz’s husband, also a respected man in the valley, who works for the Ismaili society in the area.

I felt the modern thinking of this sect, when I met a villager of Krat one day. This old man, in his first words, asked me, “How many years you read in the school? Do you have father and mother?” instead of the common question in other parts of Afghanistan, “Are you Muslim?” In fact, never once I was asked my religion by the villagers in Wakhan. For them my religion is not important. My education and my family were more interesting thing to know.

Actually it’s not only about freedom which the Ismaili people of Krat village in the Wakhan Valley concern about. Life here is difficult. Shadowed by the mystical snow peak of Baba Tangi, water is always pure, clean, and abundant. But rice, the staple, is not grown here. The truck bringing rice from lower city of Ishkashim comes without fixed schedule. Road is very bad. People here are much more luckier than the Sunni Kirghiz ethnic further in unaccessible high mountain areas of Pamir.

Only wheat (gandum) is available, as well as some kinds of vegetables, and milk – self-supplied by the fields and cattle. Meat is luxury food. Men doesn’t have much work to do. Women collect wheat and grass for fire. Young boys collect stools of cows or woods. Young girls collect water from the spring. They don’t need Barbie dolls. Little girls of 5 years old already have a real baby brother or sister to carry around. Men sometimes work in the field, sometimes with the animals, sometimes with the stones or wood. But most of the time, people here are idle, sitting and chatting around.

Bulbul, his name is a type of bird, might be one of the luckiest men in the village. He got the responsibility of providing tea and bread for the Pakistani workers, everyday at 6:30, 9:30, and rice at 12:30. The halves of the clock were caused that the Pakistanis still prefer to use their time instead of Afghan time, 30 minutes behind. He earns 4500 Af (90$) per month per Pakistani worker. There are 15 workers, so he is supposed to get 1350 $ per month. The wheat , tea, and rice are provided by the Pakistanis, so his task was just to prepare the food. And it was actually his wife’s task.

I went to Bulbul’s house everyday with the Pakistanis for breakfast, tea-time, and lunch. The Pakistanis sit in the guest room. Sometime I was invited to the private part of the house. Bulbul is married but has no children. In the private house, as it was an extended family system, was full of children. The stove (bokhari) of the kitchen is on the ground and the family sleeps in the same room as the kitchen. The walls had a slice of oil, collected after years of cooking. There is no electricity here, light comes from natural source – the sun, which pass through a big window on the roof. Bulbul’s house is quite a rich one. The window on the roof has door which can be closed by the help of long stick. Other houses use plastic to cover this window when rain or snow comes. The stove is open, without chimney system, and the room is full of dangerous gas when cooking time comes. I remembered chimney has been introduced to their Wakhi brothers in Chapursan. It has not come to the isolated part of Afghanistan yet.

Bulbul has 3 brothers and they live together in the same house, no partition. The two brothers and family now are in Pamir, herding the yak and sheep to the higher mountains as the animals cannot survive the summer heat of Wakhan and prefer to grass in the colder, higher Pamir. Pamir is 5 day walk away from Wakhan. The way of life of Wakhi Tajik, where part of the family reside in permanent place and some other part move to other areas periodically and come back to their permanent house for some seasons, is semi sedentary life. The Kirghiz in the Pamir maintain semi-nomadic life. They have two permanent places, one for winter and one for summer, and they commute between the two places during the year. The nomadic life, for example of the Mongols in Mongolia, where people keep moving to all possible places during their life, doesn’t exist anymore in this part of Afghanistan.

The women in Krat are all wearing traditional dress. It consists of cap, scarf, shirt, vest, skirt, trousers, and shoes. All are beautifully embroidered. The women also wear beautiful accessories: colorful necklaces and pins. Bashbegim, Bulbul’s brother’s wife, wear a dozen of necklaces and a pair of pins written ‘Muhammad’, the name of the Prophet. Other women may also bear the photo of their husband together with keys, nail cutters, star shaped accessories, hung on the front side of the vest. Such accessories like these are not worn by their Wakhan sisters in Chapurson (or Chapuristan as it’s called in Wakhan). Some said it was sinful (gunna) to wear to many accessories.

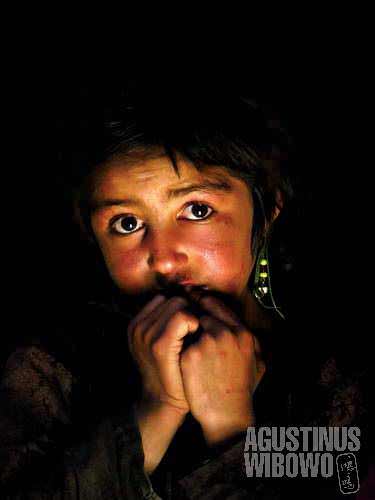

Usually each house has an open air hall, where the women of the house use to weave, make clothes, or to breastfeed the babies. When I visited Bulbul’s house, his wife was busy of boiling the wool strain with color powder. Snow starts to fall a month later, and it’s the time now to make warm clothes for the children. Bibi Roushan, another woman in the neighborhood, was also busy of weaving and sewing, while her baby slept calmly in the baby cradle (katq). The women in the village also have the responsibility of collecting grass, wood, and wheat for food making. One day, when I was taking a nap in the hall, the window was knocked by a young girl, whispering “Aks! Aks! (photo! Photo!)”. She was with her grandmother and sisters. They posed happily in front of the camera while picking the grass among the wheat in the field, to add more taste to the plain rice dinner. The Ismaili teaching didn’t restrict them from interaction with strangers, something which is bizarre to be done by Afghan women in other areas. Somehow they reminded me to Indonesian village women who also often actively asked to be photographed. I do really enjoy the warmth of hospitality here.

It’s really only hospitality which rules the people of Wakhan Valley. When meeting each other, it’s compulsory to ‘sing’ the long greeting, “Salaam aleik, chetorasti? Khob asti? Jor asti? Aram asti? Bakhair asti?” All just ask whether the other person is fine, safe good, and happy. The people, despite of their poverty, also like to share meals and tea with guests. When taking food or drink, it’s essential to offer the other people around first before actually eating or drinking. They usually take plain bread to be eaten with salt milk tea. For lunch or dinner, it’s usually rice with cheese. Never once I was asked to pay for my food during my days in Wakhan. I regretted not bringing anything to share so I don’t know how to reciprocate their hospitality. I only took photos which made them really happy when seeing the result on the monitor, and said, “tashakor, zahmat dadam, muftah khordam,” expressing my grateful and regret to be a free loader.

And often because of this hospitality culture, I felt really ashamed. Once I told Faizal I needed to recharge my batteries. Electricity is really a big problem here. There are only 3 generators in the village of 450 people of 35 families. One in jamaat khana, no plug. The other in the house of the rais (the village;s chief), temporarily broken. Faizal brought me to Akimboy’s house. He asked permission in Wakhi. I didn’t understand.

“He is a good man,” said Faizal to me.

Later I found they didn’t turn on the generator everyday, but they would do it especially for me. To save my face, instead of saying I needed to recharge, Faizal said we wanted to watch Afghan songs from the VCD. Akimboy brought the TV and VCD, and a bunch of CD collection from the storage room. It ended up to be TV show (attracted some other boys from the neighborhood to watch the movies), a dinner, accommodation, and breakfast the next morning. We were really ‘muftahkhor’, free-loaders. By the way, the movie that night was an Afghan-made movie about a foreigner (khareji) driving a UN car to bring medicine (miraculously without body guard parade), being looted by the mujaheddin then saved by a woman fighter named Malalai who brought him to Pakistan border. Malalai was a great heroine in Afghan history and now commonly become heroine of stories and movies made in Afghanistan. Akimboy turned on the generator for 4 hours, enough for me to recharge all of my batteries and for the guys to watch songs and movies. The dinner even included fried meat and meat soup, a real luxury in Wakhan.

Akimboy is among the richest in the village. He has dog to guard his house. He lives with other 2 brothers: Baranboy and Qadam. All are married and have children. The house is full of babies. Rashida, 2.5 years old, Akimboy’s daughter, is a good dancer. When the VCD played happy Afghan music, she danced in front of the TV. Her face is always dirty as she never stops sneezing. In the morning, 6:30, it’s time for the little girls to feed the cattle. The family has two cows, and two girls of the family bring the beasts to the grassland nearby. The girls have wood stick and it’s amazing to see how these little babies can be also cruel when beating the cows, to prevent them get any closer to the Wakhan river or eating neighbor’s wheat. Rashida sometimes joines them, but most of the time sits at home, crawls on floor, cries, beats other smaller babies, walks around, kicks the dog, etc. Qadam, Akimboy’s youngest brother, has the youngest baby in the home, just 10 months old. In total there are 3 babies younger than 2 years old in the house for the women to look after, plus half a dozen another little boys and girls. It’s not important anymore who is whose baby, the baby becomes responsibility of all women in the house, included the grandmother.

Wakhi Tajiks have interesting culture to make the babies sleep. First the mother ties the baby on little hammock, then swings the baby slowly until it falls asleep. The tying stuff is to prevent the baby fly away or fall down. Akimboy family has 3 babies but only 1 hammock, so they use in queue. After the baby falls asleep, it will be moved to a cradle, also swing-able. Again, the baby has to be tied still on the cradle, for safety. Than the cradle is covered by curtain to prevent the light annoys the little angel’s sleep. The baby sleeps like this until it reach 2 years of age, when he or she starts to sleep on the floor just like their parents and elder brothers and sisters.

The morning grazing time ends at 10. At 11, the little boys and girls of each family bring the family’s cattle to the huge grassland east of the village. Suddenly the grassland turned to resemble an animal market. About a hundred of cows, sheep, and donkeys, the possession of all villagers, are grazed then collectively to grassland far away behind the mountains in upper area. The men of the village have turns of who has the responsibility to bring the animals of the village to the grassland. The little boys and girls, the young shepherds of the families, then return home for lunch. They will be back to the village grassland to pick up their own animals after the collective grazing at 4:30 afternoon. Why the animals should be brought collectively out of the village for grazing? The fields near to the village are too precious for the wheat production and for sure a hundred of cattle would affect the land fertility tremendously.

While people concern so much about the cattle and field, it seems that almost nobody knows about his or her own age. The people are not educated so they don’t think any importance of remembering birthdays. Daniar, son of Daulatboy, Akimboy’s relative, said that he was 3.5 years old, but at least he was 10 years old. He doesn’t have any concept of time dimension. The oldest man in the village, Rajabmat, claimed he was 95 years old, but it’s difficult to attest this. Another man supposed to be older than him, Tila Khan, said he was only 80 years old. Nevertheless, time is not important here, as every summer, every winter passes routinely without any drastic changes to the life in this isolated valley. Time passes as slow, as fast, as it wants.

But the more educated Wakhi brother from Pakistan side, the builders from Chapursan (called by the locals as Chapuristan) have stronger concept of time, and their existence here is supposed to bring changes to the valley. They, 15 people, mosetly stone breakers and constructors work together with the locals to build a school (maktab) in the village. Until now children has to go to the UNICEF tents in the neighboring village.

Faizal u Rahman is one of the Pakistani workers here. He earns 1000 Af (20$) per day working in this isolated area, much more than what a builder may earn in Pakistan. I spent two nights with these builders in their basecamp, a house near the prayers hall. I’m happy to speak Urdu again, but at the same time I speak Farsi to the villagers, and speaking two foreign languages at the same time makes my words bizarre as I kept mixing words of the two languages in every sentence. The Chapursan workers share the same language with the local people, the Wakhi language, a dialect of Tajik Farsi language.

The Pakistani workers still use Pakistani time, 30 minutes ahead of Afghan time. They start work as early as 7, and finish at 5. The stones for the school building are broken from the mountains, then transported to the construction are a by the tractor driven by the Chairman Juma Khan. They have tea-time and lunch at 10 and 1, in Bulbul’s house. For afternoon tea-time it’s responsibility of another villager and for the dinner of these 14 workers, the houses in the village each has their turn. Afternoon, for time passing, they usually play cards and listen to radio. The radio can catch as far as Thailand broadcast. Once they were listening (without understanding) to a Chinese broadcast, a news about inauguration of a hospital in a village deep in Guangdong province. I felt I was among the Chinese workers now.

The Chapursani share the same culture, same faith as the villagers of Krat. But being raised in different countries, the same ethnic has walked different fate of life. The Aga Khan organizations has brought much development to the Ismaili areas in Pakistan, brought a high literacy rate more than 90%. The Ismailis of the isolated Wakhan corridor are awaiting for drastic change for their future. And they are sure, they don’t need wait too long anymore.

Good One

I am a Wakhi from the same area you visited. Very wonderfully written and the pictures are very great. I need your permission if I can use your pictures and the contents to preent my culture here in Germany. I am doing my Masters in Stuttgart Germany.

WARMS REGARDS and THANK YOU FOR VISITING OUR AREA…

You are always welcome

MUHAMMAD ALI (muhammadali.shupun@gmail.com)