Ashgabat – Ruhnama, the Book of Soul

“The Turkmen people stayed without their guardian”

– Diyar Magazine 1, 2007

Being in Ashgabat means being unable to escape from the eyesight of the great Turkmen leader, the Head of all Turkmens, the Great Saparmyrat Turkmenbashi. On every corner of the capital you would admire the beautiful golden statues of the leader, in every different position: standing, sitting, reading a book, welcoming the sun, raising one hand, raising both hands, and all other patriotic poses. Commenting about these statues, the Great Turkmenbashi once said that actually he didn’t want to build statues for himself, but as the Turkmen people wished to have the statues, so he didn’t have other choice than to flourish the city with his statues. Not only statues, you would see also slogans, quotes, and boards of the books he wrote.

Near every single statue, there was at least one soldier guarding this golden leader. These statues were sacred; nobody was allowed to get close by, not to mention to touch it. I accidentally took a photo of a golden statue of the standing leader under an arch and patronage of five-headed eagles – the presidential symbol of Turkmenistan. My action raised anger of the guard. He asked me whether I took photos. I said no. I left away. At the other end of the road I was stopped by another guard. He already got information of my action from an amazing information web among the intelligence. I was brought to the central office and there was senior officer asked me to show the photos I had taken.

I just turned on my camera without changing the preview mode.

“You see, there is no photo at all,” I said.

“You didn’t take any photos today?” he seemed not believing me.

“No. The day just started. And it is too cloudy to take photos.”

I successfully escaped this way. I walked again. But when I reached the other corner of a street, another guard stopped me and asked me to go back. I was impressed by the work of the intelligence service they have. I thought, even if I stopped in the bazaar and ate in a restaurant, these people would know anyway what food I ordered.

This time the police noted my name, nationality, date of birth, passport number, etc. I would not be surprised if this information would be sent immediately to the intelligence center and all security agents would know about me, a ‘spy’ who took picture of a golden statue of their leader and pretended not to.

In the country when almost everybody was trained to be a spy, anything could happen.

I was not paranoid, if then I ran back to my room, scrapped all of my writing in my diary about Turkmenistan, torn every page to smaller parts, and distributed the notes in various pockets of my trousers and jackets in my luggage. In fact, I was happy that I did it, as later when I left the country, I was searched thoroughly and the border guards asked me to recount the contents of all books I had.

What made these people, the army and soldiers as well as the majority of Turkmen citizen, willing to do everything to defend their leader? What made the leader occupied the heart of everybody here? Was that because of love, belief, fear, submission, or just merely a habitual?

Ashgabat was incredibly guarded by enormous number of police, soldiers, army, guards, and all kinds of uniformed officers. The traffic policemen did not only have to control the traffic, but also to give salutation to all cars with government plate number. Such submissive respects were given to ALL government officers. The soldiers were everywhere to keep the security of government, installations, and president statues (maybe they afraid that the gold will be stolen?) The police strolled around the streets, patrolling, as well as checking people’s documents. It was always a mixed feeling of being safe, as one wouldn’t be afraid to be robbed on the streets, as well as feeling of fear, as every single motion was watched by invisible eyes. Your every single breath is watched, and especially after you committed something undesirable (like taking pictures of the beloved leader).

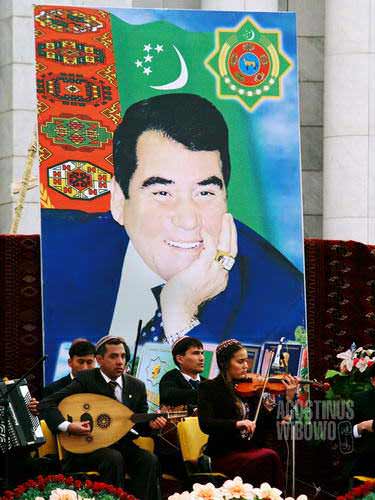

I remembered those songs and dances praising the great leader and the great book, Ruhnama. I also felt the feeling of pride, affection, confidence of the folk, as well as boredom towards this routine (a student in concert and a man in bazaar asked me, “in you country you see your president’s photos everywhere like here?”). No matter what you wanted to feel, you wouldn’t be able to escape the fate of seeing Turkmenbashi whole of your life.

In Indonesia, under Suharto regime, people used to say, “Once you enter the territory of Indonesia, Suharto and his families’ dirty hands are already plucked inside your pocket,” referred to totality of corruption monopoly of the regime, which rip you off from your every single breathe in Indonesia. From the toll road, airport tax, until car tax, TV tax, even dog tax, instant noodle, telephone bills, everything goes to enrich Suharto’s pocket.

Turkmenbashi, in different sense, conquered all corners of people’s mind. First, as Kemal Ataturk in Turkey, he claimed himself as the father of all people living in his land. If ‘Ataturk’ means ‘father of all Turks’, then Turkmenbashi means ‘the Head of all Turkmens’. Then this very head appeared on all Manat banknotes and coins, TV broadcasts, street signboards, compulsory Holy Book, and big advertisement boards. In single word, nobody was allowed to forget who the man here was. Villages, cities, ports, streets, airports, even days and months were all renamed to bear his name, his family members’ names, and the concepts he created. The Caspian port town of Krasnodovsk was renamed Turkmenbashi, the border town of Charjou was renamed Turkmenabat, and the town of Kerki was renamed Atamurat – Saparmyrat’s father. The month of April was renamed Gurbansoltan Eje – Saparmyrat’s mother as well as national heroine. Don’t forget Turkmenbashi (new name for January, the beginning of the year), Baydak (means flag, February), Nowruz (means new day, to mark the Persian New Year in March), Magtymguly (Turkmen poet, spiritual leader of the Turkmen people as Turkmenbashi stated in his Ruhnama book, May), Oguz Khan (the founder of Turkmen, June), Gorkut (Gorkut Ata, historical hero, July), Alp Arslan (another idol creature quoted in Ruhnama, August), Ruhnama (the infamous spiritual books of the Turkmen, September), Garashsyzlik (means independence, as Turkmenistan Independence Day is celebrated in October), Sanjar (another among the Turkmen praised heroes legitimized by Ruhnama, the last king of Seljuk, November), and Bitaraplik (means neutrality, of which Turkmenistan proud of to be. The Neutrality Day is celebrated on December).

If that was not enough, Turkmenbashi also offered a new set for the days: dyncgun (rest day, Sunday), bashgun (main day, Monday), yashgun (young day, Tuesday), hoshgun (happy day, Wednesday), sogapgun (blessed day, Thursday), Annagun (Friday, taken from Persian word), and ruhgun (spirit day, Saturday). The new names of months and days were announced on August 10, 2002. It is used in all government media, and I bet the propaganda made by the government made it faster for the people to change their mindset. For me, I had many problems in understanding the dates given in a Turkmen magazine I bought from the post office.

If other Central Asian republics’ citizens have to get used with the change of the names of cities and streets from Russian names to be more nationalist ones, the Turkmen had to exercise this much often until they became completely lost and don’t bother to know the names for today. For example in central Ashgabat, the main street names were Azadi (independence), Magtymguly (Turkmen poet), Atamyrat Niyazov (Turkmenbashi’s father), Bitarap Turkmenistan (Neutral Turkmenistan), and last but not least, Turkmenbashi Street. These names were changed again, in 2002, when Turkmenbashi had ideas he could understand by himself. The weird names were now replaced with weirder number, like Pushkin Street was renamed 1984. You may encounter street names in the city as 1988, 1998, 2004, 2008, etc. If I had been the city dweller, either I would have been a historian or mathematician, or I would have never been able to remember the new street names changing in daily basis.

Besides those, the invasion of slogans and concepts on all corners of the city was a kind of brain ‘purification’. One should know that ‘Ruhnama is our way of life’, and ‘Turkmenistan is an independent and neutral country’, and ‘Turkmenistan is of people, homeland, and Turkmenbashi (compare to Hitler’s ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Fuhrer)’, and many other things. The slogans of golden era, freedom, neutrality, Ruhnama, great leader, reminded me to the propaganda in Indonesia during Sukarno and Suharto time about our golden gate to prosperity, our ‘bebas aktif’ and ‘non-blok’ foreign policy, about our father of independence and father of development, as well as our Pancasila – the one and only ideology and way of life of the Great Indonesia.

It’s available in all languages. And it has been launched for the E.T, UFO, aliens, and their gangs out there.

All of these are written in the Holy Book. If Indonesia had Pancasila then Turkmenistan offered Ruhnama. Wait. Don’t get me wrong, this is not a religious holy book, as Turkmenbashi stated many times in his book. But, “this is a good book”, as he claimed. On the entrance gate of the Turkmenbashi Spirit Mosque, built at the birthplace of him in Gypjak and to be the pilgrimage site of all Turkmen Muslims in place of Mecca, it was stated “Ruhnama Mukaddes Kitapdir, Gurhan Allahin Kitaby (Rukhnama is Holy Book, Koran is God’s Book)”. This ‘mukaddes’ book then had the authority to force all the citizens of the glorious country to read, memorize, and learn the spirit, in order to survive. Not many countries like Turkmenistan force taxi drivers to pass an examination on Ruhnama to get driving license. (Well… Indonesia was among these few numbers of countries, where all students had to study Pancasila since baby time until be graduated from university, and everybody needed to be ‘Pancasilaist’ to get a proper work. Students and workers in Turkmenistan had the same fate with their Ruhnama).

Not only affected the job seekers, Ruhnama also intruded the spiritual life in Turkmenistan. Ulemas in mosques also give speeches about Ruhnama and this book was placed together with the Koran. In Indonesia, in 1970s, ulemas who didn’t agree with Pancasila as the single ideology were kidnapped and got ‘special training’. What made Turkmenbashi more adorable with his Ruhnama was his claim, “I asked Allah that for a person who reads it three times – at home, at sunset and at dawn – to go straight to heaven.” I wanted to go to heaven, so I grabbed a copy of Ruhnama in English, and I read three times. But I didn’t think I was approved, as I failed my Ruhnama exam online (Ruhnama Quiz). I even didn’t have the right soul to believe that united ants could defeat a tiger.

It might be not quite significant if Turkmenbashi raised a monument in the shape of the pink book in the bizarre new area of Berzengi as well as other boards in the city. The significant point of Rukhnama (Rukh/Ruh = spirit or soul, nama = letter, literally means book of soul), the book which was made to prepare the soul of the Turkmen citizens, was how it applied to ‘purify’ everybody’s spirit. A visit to a government’s book shop was always interesting. Ruhnama conquered most portions of the bookshelves. The green and pink cover book (first edition of Ruhnama) was not only available in Turkmen language, but Englih, French, German, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Hungarian, Czech, Korean, Hindi, and even Thai (no Javanese version yet to respect our Javanese king Suharto). Turkmenbashi was more than confident to export his ideas to international world, as well as letting the unidentified creatures from the outer space to read his masterpiece (on August 27, 2005 Turkmen government claimed that ‘Ruhnama already conquered outer space’ when Russian rocket Dnepr sent a special container with the scared symbols of Turkmenistan: flag and unique philosophical work of Niyazov Ruhnama to the near-earth orbit from the Baikonur space center. It was claimed as the triumph of Turkmenistan’s policy based on wise traditions which brings ideas of humanism and peace into the world), but he was more enthusiastic in providing more reading material to his citizen by writing the second book of Ruhnama (Ruhnama Ikinji Kitap).

The bookstore was not only flourished by Ruhnama, but Turkmenbashi’s other books as well, like “You are a Turkmen” and “The Fate of Turkmen is My Fate”. Then it turned for busy school teachers to order big quantity of these books from the bookstores, read and study it deeply, and teach the students what the Leader wanted them to know. The book was not expensive. A hard cover Ruhnama with 400 pages (all with paper-wasting big font writing) cost 50,000 Manat (about 2 dollars). As ‘good’ and ‘holy’ reading material was available at affordable price, it was hoped that the Turkmen would have better preparation and power to reach the goals of their Golden Age. As Turkmenbashi stated, “Ruhnama should be a source of power that will keep hearts alert, of intellect, and suitable spirit, and the poetic soul of those real Turkmens who are concerned with their own spiritual world and also their spiritual and physical development.”

The book was started by a picture of the smiling president, plus the flag, coat-of-arms, and presidential symbol of Turkmenistan. Turkmenbashi started his speech by saying “In the name of ALLAH, the most exalted … … This book, written with the help of inspiration sent to my heart by the God who created this wonderful universe and who is able to do whatever He wills, is Turkmen Ruhnama”. God had inspired our Great Leader Turkmenbashi to write this sacred book. This book was as sacred as Koran for the Turkmens. I really didn’t expect that I annoyed the passengers in train when I tried to write some notes on my Ruhnama book. “Why you do that? It’s a ‘good’ book,” said a young man. Yes, it should be placed in higher place, should be treated as Koran. You know Koran? The Holy Book. “You should not scrap the book, write on it, and you always have to put it on higher place,” said another teaching me how to handle this sacred book.

My impression of Ruhnama, it was not a religious book, but the way it was stuffed to the minds of the people resembled a pseudo-religious material. It was supposed to be believed by faith, no discussion allowed, and everything was right with no debates. The first part of the book tries to build the nationalism and pride to be Turkmen. It is about a pride to be a great nation that conquered the world for centuries and once to be the greatest nation on earth, a pride to have the long history and brave blood, a pride to have a beautiful flag (Turkmenbashi put the design of Turkmen carpet on flag which made Turkmen flag the most sophisticated flag today), a pride to have a rich language and powerful Altheke horse (this horse also made its way to the Turkmen coat-of-arms), and the pride to be united as a free, independent, and always neutral (not always Coca Cola) Turkmenistan. The book incorporated the history of Turkmens, being the descendants of Oguz Khan, which they claimed as Father of Turkmens. The Turkmen, said the book, then conquered the world with their Turkmen dynasties (historians might disagree) from Tuluni, Atabeg, Bori, Zenni,, until Seljuk, from the territory of Turkmenistan until Armenia (Sokmen el Kutbi), Iran (Salyr dynasty, Gutlug Khan, and Qajar), Khorezm (Il Arslan and friends), Turkey (Ottoman dynasty), Azerbaijan (Garagoyunli, Akgoyunly), until Afghanistan (Ghaznavi dynasty with their great kings of Sultan Mahmud and Sultan Massoud) .

It was indeed a powerful book. I read the book and fell asleep. In my dreamt I saw my soul glowing with all of the pride of being a Turkmen (it was just a dream, I am not Turkmen, but I shared the pride after studying the book). Well, this is not something new in Central Asia. The creation of new nations in the huge mass land which never learned about rigid borderlines of countries in their pre-Russian era, now found themselves to be solid single nations. Every nation had to build their nationalism, their values of being a nation, and their reason of existence. If Turkmenbashi claimed all conquerors who spoke Turkish language as Turkmen (Turkey spoke nothing when their Ottoman empire was claimed as Turkmen), then the little Tajikistan, a country artificially created at the fringe of Uzbekistan, claimed all Persian-speaker great men as their Fathers (Rudaki, Ibnu Sino/Avicenna, Ismail Somoni, Alisher Navoi, etc), as well as confronting Uzbekistan of possessing the Tajik speaking cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.

Kyrgyzstan, another tiny, isolated, new nation around the Tienshan Heavenly Mountain Range, celebrated the 3000 years of Osh city, the emerald of history, and 1000 years of Manas. When were the Kyrgyz 3000 years ago? They might forget the great king Babur, in his legendary travel writing Baburnama, noted when he visited Osh, the people of Osh went out from their homes to the streets to see the strange mountain people (the Kyrgyz people today) went down from the mountains to the town. Manas even pre-dated the Kyrgyz.

Kazakhstan, a huge country but with less obvious civilization as their culture of being nomadic, recently made a big investment by making the glorious film of Nomad (Kochevnik), directed by Sergei Bodrov, Talgat Tamenov, and Ivan Passer, official entry from Kazakhstan for Oscar’s best foreign language movie competition 2007, brought the pride of glorious history of Kazakhstan, on their possession of Turkistan, and claimed the Kazakh as the most advanced nation in Central Asia. Turkistan, located at the fringe of huge mass land of Kazakhstan at the border with Uzbekistan, with an architectural heritage the rest place of Khoja Ahmed Yasaui, a learned Sufi teacher of 12th century, born in Sayram (now Kazakhstan territory) but studied in Islamic school in Bukhara (now Uzbekistan territory) showed more Uzbek in term of settled civilization rather than Kazakh’s nomadic culture. But the border lines did not exist by his time, and he didn’t need to argue whether he had Kazakh passport or Uzbek passport. The Kazakh nationalism broad by the film, as the propaganda to the world of the ‘real’ Kazakh civilization after humiliation by Borat, caused pathetic views from the Uzbeks.

The Uzbek might claim themselves as the most civilized nation among others in Central Asia. But as creation of other nations here, Uzbek and Tajik were more Soviet matter rather than history. It was always blurry what the limit between Uzbek and Tajik was. They lived in the same areas, shared similar cultures, and despite of speaking different languages, their languages influenced each other (the Tajik spoke Turkicized Persian and the Uzbek spoke Persianized Turkic). The attempt of separating what was Uzbek and what was Tajik in post-division years was ridiculous considering these two ethnic divisions did not exist in their past.

So, Ruhnama was another story of nationalism development among new nations in Central Asia. A claim of everything speaking Turkic as part of Turkmen history to build the pride of nationhood was one of the method. Turkmen might be prouder as even the Turkish called Urgench (Konye Urgench, the old Urgench town, is located in territory of Turkmenistan now) as their Atayurt (Father Land). The fact that in Ghazni (now Afghanistan) still existed places with Turkish names were enough to say that Afghanistan was under Turkmen rules, moreover the great Ghaznavi rulers were famous for their brave action to destroy the Hindu idols in India (Sultan Mahmut was known as idol-destroyer), added more pride for the Turkmen to claim their bravery to struggle in the sake of their religion. The fact that Iranian Azeri community spoke Azeri (one of Turkic dialect) was enough to claim Iran was Turkmen under Qajar dynasty.

But this was not the sole purpose of Ruhnama. Turkmenbashi decreed:

“Every human lives with hopes and desires.

I want Turkmens to live the golden life, in the golden spirit, with pride and unity.

I want you to live with the qualities of unity, cooperation, charity, and high moral values.

I have prepared Rukhnama for the Turkmen nation to be a light and a guide on its journey towards its goal.

All Turkmens, not wasting the breath bestowed by Allah, should devote their energy, effort, and capabilities to their nation and their country in order to provide our nation with a life of well-being. Then, there will be no target that cannot be reached, and no task that cannot be accomplished.”

As Turkmenbashi wanted people to know about his book, “Nevertheless, Rukhnama must be the centre of this universe. In this universe, all the current and the future cosmic matters should go on spinning, in Rukhnama’s attraction, centripetal force, and orbits.”

To prepare the quality of his people, Turkmenbashi quoted many heroic examples of the Turkmen great men in history (including all Turkish speakers he claimed to be Turkmen) as well as heroic examples of himself, his grandfather, his mother, his father, and his uncle. What Turkmenbashi’s neighbor recounted him, then quoted in Ruhnama, about the Great Leader’s brave father was:

“… The Germans were trying to control the situation and shouting each other while holding the automatic weapons. Russian soldiers were collected in one place after throwing away their weapons. There were six of us from Turkmenistan, five Turkmen and a Russian. At that time, a friend of ours took out a piece of tobacco and wrapped it with old newspaper. We were talking it in turns to smoke it. When the cigarette came to Atamyrat (Turkmenbashi’s father), there was a Russian on his right, and a Turkmen friend said “Atamyrat, don’t give it to the Russians…”

Atamyrat said, “No, friend, this friend also fought with us and put his life in danger to save the country. He should smoke when his turn comes. There is God and we should not lose our hope even to our last breath.”

And what happened after that, the Turkmen friends told the German soldiers that Atamyrat was communist, because he gave the cigarette to the Russian, a communist. Atamyrat was shot death in front of the Turkmens. The Germans then threw the dead in the hollow.

It was a patriotic story that one would admire. We also learnt from Ruhnama many other patriotic stories of Turkmenbashi’s family members. And a reader would ‘adore’ Turkmenbashi’s philosophical words. In fact, most of the words were quoted from old wisdoms and sayings. Like this one, in chapter titled ‘A Father has the Rights of ALLAH’, he wrote (with his own credits without quoting his source):

“Every age has its peculiar properties. The child has different thoughts of his father at different ages:

5 years old: “My father knows everything”

10 years old: “My father knows quite a lot.”

15 years old: “I know as much as my father does.”

20 years old: “To tell the truth, my father does not know anything.”

30 years old: “Nevertheless, my father knows something.”

40 years old: “It would be fine if I consulted my father.”

50 years old: “My father knows everything.”

60 years old: “If only my father was alive and I could consult him about this and that, I should have appreciated him properly when he was alive.”

The preparation of the soul of the Turkmens that Ruhnama tried to achieve, besides the pride of being united as Turkmens, was also how to behave as a father or a mother to his child, a child to his parents. He described that a father had the rights of ALLAH, none would care as much as my mother would (in this chapter he even quoted Eve and Jesus Christ’ mother), and children as continuation. He also wanted to see the smiling faces of Turkmens, as he said, “A smile can make a friend for you out of an enemy. When death stares you in the face, smile at it, and it may leave you untouched, I believe.” There were many more moral teachings in Ruhnama, most of them was quoted without even crediting the sources, both useful or incredebly useful life conduct like : “chew on bones like dogs and you will have strong white teeth, not gold implants.” Ruhnama reminded me to our philosophical way of live: Pancasila. Everything was idealist, unreal, and would have function in utopia.

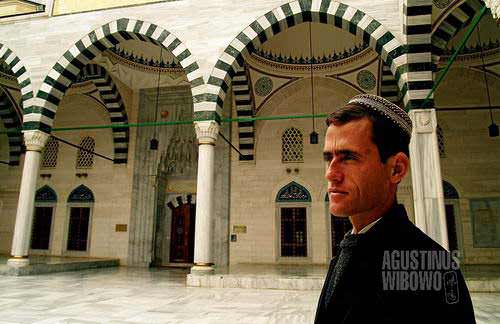

Turkmenbashi indeed created a utopia for His people. The dream of living in a place where oil was even cheaper than water and everybody should not worry about live because they had a Guardian (that was him) who protected them and guided their future. People were not rebellious because he succeeded to make him quiet. He also used God for his politics. Turkmenbashi was known as a secular leader, but his pilgrimage to Mecca didn’t only bring much petrodollar to flow his country, but also the modern Azadi Mosque (which architecture resembled Blue Mosque of Istanbul) and the giant Saparmyrat Hajji Mosque (which he claimed as compulsory place for pilgrimage – he was then buried here). The mosques were always deserted. The characteristic of the Turkmens, due to their nomadic history, was more suitable to be secular rather than religious. The sudden conversion of the president from communism might be followed by some, like those veiled women who delivered their prayers in the middle of busy bazaars, but not by most others. A girl who worked in a restaurant in bazaar claimed herself as a Muslim, but when I asked whether she performed prayers, she answered that she didn’t know how to do that. I asked whether she knew the meaning of Laillahaillalah (There is no God but Allah) she said, “Sorry, I don’t know any foreign language.”

I saw many mirrors of Indonesia from Turkmenistan. We, too, were used to live under dictators for decades. Ruhnama was Pancasila, and Turkmen’s great history could be adapted as Sukarno’s campaign on Pan-Malaya, the claim that all Malay archipelago (included Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and parts of Thailand) part of Indonesia, which then led us to bitter confrontation years with Malaysia. We also had the slogans like “from Sabang until Merauke (that is Indonesia)”, “unity in diversity”, “One Land One Nation One Language”, etc. Turkmenbashi’s sudden conversion to Islam and sudden appearance to be religious was similar to Suharto’s story that made similar maneuver to grab support of religious politic powers. From a country which forbad the use of veils, Indonesia turned to be a country which actively built grandiose mosques in other countries (Bosnia, South Africa). From a president who insisted separation of Islam from government, Suharto became someone who supported ICMI, an organization whose mission to show that technology might walk together with Islam.

I understood as Ruhnama was not a bad book. It tried hard to unite a new nation, to ‘guide’ them to proper way, and to provide them a pride of being a new entity. It was the same as Pancasila. What made Ruhnama different was: the pride, the respond to it, was much more than bizarre and unnecessary. Rather than being a philosophical way that people should dig deeper, it turned to be a ‘Holy Book’ that people should worship spiritually. Turkmenbashi insisted it was neither a religious book nor a history book, but the attitude he wanted his people to behave was different in other side.

The Great Great Great Saparmyrat Turkmenbashi, the author of the mukaddes book of Ruhnama, passed away due to heart attack December 24, 2006. The Turkmens, those who voluntarily or forced to worship him, suddenly was in limbo, got lost in the world jungle. From a magazine shop (of which most magazines and newspapers only pictured the president’s photos and government official announcements) I picked up a very colorful magazine. This is Diyar, a renowned magazine which was founded by “the President of Turkmenistan Saparmyrat Turkmenbashi the great.” January 2007 was a mourning edition. The cover had the picture of the beautiful Turkmen flag as well as a big photo of the president. There was text in 3 languages (Turkmen, Russian, English), saying:

“The Turkmen people stayed without Guardian

Saparmyrat Turkmenbashi the Great

The first and life long President of Turkmenistan

The Great Son of the People and their Great Leader

The founder of the Independent, Neutral Turkmenistan state,

Has died.”

03/18/07 @ 12:44 by Avgustin

Type: Post

Categories: About Turkmenistan

March 18, 2006 Ashgabat – A Disneyland

Days were always cloudy and cold during my stay in Ashgabat. Today was not exception. Every Sunday, some old stamp and coin collectors gathered in front of Lenin Statue to exchange and sell their collection. Most of them were senior Russians, from 40 years to 70 years of age.

As anything else here, philatelic and numismatic hobbies in Turkmenistan also went to bizarre way. The post office didn’t sell stamps more than for postage purpose. The stamps were printed abroad in limited quota, sold to some government officials who would then distribute the stamps through their own channels. This made Turkmenistan stamps incredibly difficult to get in their own country. Sometimes it was even easier and cheaper to buy Turkmen stamps in Russia rather than in Ashgabat.

Mikail might be the youngest collector among those gray-haired old men in the park. He invited me to his house, some blocks north, to see his collection. “Life here is difficult, we don’t have money and work,” he grumbled. As a Russian, it was difficult to get proper job here. “If you don’t speak Turkmen, you cannot work. Everything should be written in Turkmen. I only know Cyrillic and it is still difficult for me to write Turkmen Latin. I live here for 40 years but still don’t speak the language.”

Mikail was typical of Russians elsewhere in Central Asia. Being Russian somehow prevented them to dilute with local majority. Was it due to their arrogance to learn language of ‘the lower nations’? Or was it due their inability to break the exclusivity wall between them and the people of the colony lands? In anyway, these Russians suffered a lot when some Central Asian countries, especially Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, declared their nationalism-building programs. The programs included forcing all people to speak the national language in their works, thus refused the Russians who don’t speak local languages in fields of works.

For the case of Mikail, he had a Turkmen wife from Turkmenabat (Charjou), he worked in the bazaar, and Russians were now very small community after the independence of Turkmenistan, as most of them left the country immediately. His life couldn’t be separated from Turkmen breathe, but he just couldn’t speak the language. That’s all. And that was which made him suffering.

Before that era of ‘nationalism’ euphoria after the independence of the country, Mikail was specialist mechanic of marine boats. He mentioned Aral, Caspian, and a river south of Baikal as the places where he ever worked. Now he was reduced to a simple vegetable seller in the market. Some people might say the country’s policy was important in building nationalism among the newly-independent countries. Some might say they were racists. The poor Kyrgyzstan had to review their policies and forced to adopt Russian as second language in the new law reform as the Russian population, with average higher education and proficiency compared to the Kyrgyz, couldn’t get proper work to apply their ability. They were not accommodated in the country’s life. This caused backwardness in the country’s economy and stimulated many protests. Turkmenistan, in comparison, was still much richer, sitting on billion barrels of deposit of oil and enjoying their Golden Age. There was no big need to consider these half-unemployed Russian minority, the people who once colonized their land.

Having a wife from Turkmenabat also offered some other problems to Mikail, who live in Ashgabat. As in the communist era, there were still many laws to prevent people migration, even inside the country. His wife still couldn’t get Ashgabat citizenship that she couldn’t get any government work here. She was also now, a vegetable seller in the Russian market.

How much was the income for people with proper work? Mikail’s neighbor, an Amernian guy who worked as a policeman who was patrolling in front of the American embassy, earned about 120$ per month. Mikail said it was little, but not too bad. At least oil and gas is cheap here, and this was a key point of life in Turkmenistan.

“You know the price of a liter gasoline here? 300 Manat!”

300 Manat was about 120 Rupiah, about 1.40 US cent.

The Turkmenbashi regime really tried to share the oil wealth to the people, a way to make citizens content, while at the same time reducing the freedom of people in other sectors. While drinking tea and looking at the Turkmenistan ‘propaganda’ stamp collection, Mikail told me about luxurious cars buzzing Ashgabat roads, corrupt government officials, the US embassy attaché who earned 5000 dollars per month but bargained hard for 5 dollar stuff, about Turkmen citizen who had to pay 40$ now for visa to visit Russia, about the new Disneyland, and about his daughter who was going to have performance there, and about anything.

From Mikail’s house I went to Tolkuchka Bazaar, which was often refered as the biggest and liveliest bazaar in Central Asia. It was located 8 km outskirt of the capital, and Sunday, the bazaar day, always caused traffic jam of shared taxis and old buses from and to the villages.

Most parts of the bazaar were just like another bazaar things, selling products from woman bras to garment materials, from torchlight to broken old TVs from the 1970s. The most interesting part of the bazaar was the carpet bazaar, where beautiful Turkmen carpets (which made their way to their beautiful Turkmen national flag) were hung and spread over the dust of the desert, open air. The village women wore traditional costumes, a typical of desert dresses: colorful, heavy, full of accessories. Some men wore traditional telpek. I bought a tahia for myself which cost only 20000 Manat. Even in this bare desert, the Golden Age of Turkmenistan was still reflected from the golden teeth of the old men and women.

Mekan Ataliew was a telpek seller in the bazaar. He was so proud that his father was chosen as telpek maker to make special hats to be presented to the Indonesian president, Mr. Soeharto, when he visited Turkmenistan at that time. “Turkmenbashi presented Soeharto the telpek that my father made. I still keep the newspaper and magazine scrap about that,” proudly he told me.

I didn’t know that our Great Leader, Soeharto, made his picnic holiday to Turkmen deserts. But thanks to him, Mekan was very happy and insisted me as an Indonesian to receive a gift from a Turkmen citizen: a high quality hand-made black telpek, good for summer and winter time. Good quality telpek cap is not hot in summer. Maybe he also shared similar feeling, perasaan senasib seperjuangan, of living under dictatorship? For Mekan, it was out of questions. For him, Turkmenbashi was a very good leader and he expected Suharto to be the same. I didn’t want to ruin his family pride by telling him how Indonesians disliked Soeharto.

The bazaar started to go back to its desert nature at 3 pm, when sellers rolled back their carpets and prepared to go home. Some grumbled of not selling anything today, but most were happy. The highway to Ashgabat was crowded by buses, cars, horse charts, and shared taxis. Back to Ashgabat, again, the slogans of great leader (Turkmenbashi), great book of life (Ruhnama), the golden age (Altyn Asyry), Independence and Neutrality (Garashsyz we Bitaraplik), being pumped back again to your mind. I went back to the city center to visit one of the ex-president’s wonder: Turkmen Disneyland.

The project was held to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the independence. Many houses were demolished and people, who once lived in the area now the Disneyland stood, were forced to leave their houses without clear fate.

Now, the 15-year-old country had a Disneyland. It was kind of miniature of Jakarta’s Dunia Fantasi. The entrance ticket was 1000 Manat only, but foreigners had to pay 5$. I chose to admire it from out the fences. It was like collecting images of Indonesian face when seeing the Turkmen visitors queuing like troops of ants in front of a roller coaster, which was Turkmen version of Halilintar where Indonesian brothers had to queue for more than an hour before the ride. The other rides that I could see were Turkmen style of Indonesian Dunia Fantasi’s Niagara-gara, Ontang Anting, Si Kora-Kora, et cetera. I wondered whether Turkmenbashi ever had a wife whose dream was to build another park to collect the desert tribes, or a flower park to collect various cactuses and orchids from all corners of the country. Almost two decades ago, the Madam Suharto made ambitious and controversial projects of building Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Beautiful Indonesian Mini Garden) and Taman Anggrek (Orchid Garden) which also left thousands homeless.

It was a Fantasy World. It was a Disneyland. One was in the middle of island in the middle of ocean. The other was in the middle of desert in the middle of nowhere. Both were fantasies, dream of being said wealth nations, and both sacrificed their own citizens.

Returned to the park yesterday I attended the concert, there was another concert for today. This park name was Great Saparmyrat Turkmenbashi’s Golden Age Park. With the tahia I bought from the bazaar today, I slipped easily into the crowd of university students without attracting police attention. The weather this time was very windy. Strong, cold wind blew from all directions. The beautiful Turkmen flags wave proudly, but the students who had to hold the flags grumbled for their unlucky fate. They had to look good on the TV though, so they kept the smiles. It was bad luck for the students who were chosen to sit at the front seats, as they would be shot by the cameramen all the time. They had to keep their good manners, smile properly, cheer in order, while a row of girls with flowers had to wave the little flowers to follow the melody of the music praising Ruhnama, Turkmen leader, and the Golden Age. All of the directed behavior of the concert, even for the spectators, reminded me to any TV programs of Chinese Central Television (I once attended a CCTV-4 program). Everything had to follow central directions. From the details of clothes, applause, smiles, waving hands, presenting flowers, cheering, anything, anything, had its direction in the book.

The great leader was visible everywhere. The stage had a big poster of Mr Saparmyrat sitting with his left hand supporting his head, smiling, as he was enjoying those dancing, singing, and all praises to his greatness. The students, like the North Koreans, also had to wear badges of President’s head on their suit. It was luckier for the students who didn’t have to sit at the front seats, as they just needed to be present, to make the atmosphere lively. They chatted in groups, just like it was a school reunion program. Nobody cared about the show on the stage. Right after the announcement that the show was finished, these students were the first group who vanished from the spot. They couldn’t leave any earlier as the police were there to patrol the escaping students.

When I returned back to my home stay, the house owner just finished renovating his house. This Shiite man was proud. But he was also full of worry. Some houses were forced to vanish because of the Disneyland project. He was afraid that the fate would come on his head.

“Does your country have a dictator? Do people have to move when the government wants them to?” asked him to me, looking for teman seperjuangan, friend-in-struggle.

Life was not as fun as the Disney Land. It was a fantasy world full of sacrifices.

Leave a comment