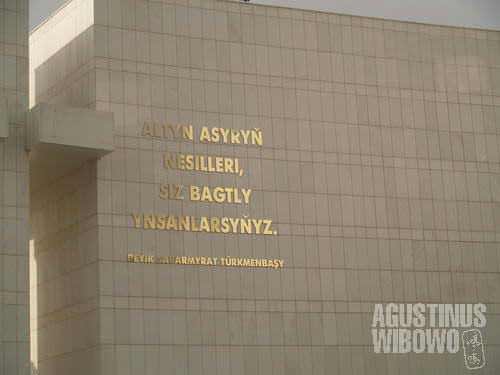

Ashgabat – The Golden Man

“The 21th century is the Golden Age of the Turkmens”

– A poster in Ashgabat

Mashhad bus terminal was as busy as the Southern Terminal (Terminal e Jonub) of Tehran. The closer the day to the Persian New Year (Nooruz in Iran, Navruz in Central Asia), the more difficult and expensive transport would be to come by. I was told that the bus ticket was already booked until the next 20 days. I was indeed lucky to get the yesterday’s ticket one day before departure, after struggling around Tehran’s various bus terminals.

Nooruz might not be the best time to travel in Iran.

The 15 hour bus journey to Mashhad cost 95,000 Rial, was still a good price for holiday season like this. I sat next to a Persian boy, Javad, from Zahedan who was living in Karaj as a student. His hometown, Zahedan, near the Pakistan border at the far south point of Iran, is home to the Balluchis. The Balluchi men wear shalwar kameez dress, just similar to the Pakistanis and Afghans. Javad wore western clothes though. “I am a Persian,” said him, the 20 year old boy, in Farsi, “not a Balluchi. I don’t speak their language and there is no need to wear that kind of costumes.”

As a Persian, Javad is a Shiite. “About 50% people in Zahedan are Shiites and the rest are Sunnis. The Balluchis are Sunnis.” About the neighboring countries, Pakistan and Afghanistan, he described his fears. “They are dangerous countries,” said Javad. I told him that I was interested in Zabul, the boder town with Afghanistan. He invited me to Zahedan, if I came back again to Iran next summer. He gave me his mobile number.

“Be careful, Zahedan can be very hot in summer! 40 degrees,” warned him.

“Don’t worry. I am used with 50 degree in Pakistan.”

He laughed.

In this trip to Iran I collected so many phone numbers from the friendly Iranians I met on road. Most of them offering stay if I visit their towns. Ta’arof or not, I was happy with all of these offers.

Our bus reached the busy bus terminal of Mashhad at 7 morning. This was my 3rd time in this terminal. Something different that today, 6 days before the New Year, the terminal was incredibly crowded.

Javad helped me to find a bus to Quchan (Ghuchan), on my way to Turkmenistan. Ghuchan was a small town north of Mashhad and along the way, I saw the other side of Iran that I had never spotted before, due to my lack of traveling in this country and limited my movement only in big cities.

It was an old bus with ageing seats. The bust fare for the 3 hour journey was only 7000 Rials. Transport cost in Iran was close to free of charge. The road was good, a fast highway. I admired that in Iran, even the roads through small villages like this one were smoothly paved highways.

The villages were quite poor and messy. There were many brown car mechanic workshops. Such messy that it looked like Pakistan. But here, in big country but smaller population, the villages were quite sparsely distributed.

Quchan was a little town that I didn’t have time to observe. I immediately went to Meydan-e-Filistan (Palestine Square) to find transport to Iran-Turkmen border at Bajgiran, 75 kilometers northward. Shared taxi to Bajgiran was 20,000 Rial, and another 10,000 to the border. It took quite long time to collect passengers, as today, Friday, is holiday in Iran.

The road to Bajgiran was like being transported already to Central Asian steppes. It was baldy hills carpeted by vast, dry steppes with some points covered by white snow. If it was not the Persian Arabic script and women walking around covered in chador, I might have forgotten that I was still in Iran.

The Iranian Turkmen border was located at the top of the mountains, the Geok Depe Mountains. It was beautiful scene here as snow-capped mountains were in all four directions. Too bad, no photos were permitted as it is border sensitive area. Some men lurking around offering Manat exchange. They brought huge plastic bags that surprisingly only contain Turkmen banknotes.

I was thinking that Iranian Rial was already among the most inconvenient money on earth, with the biggest nominal value a little bit more than 2 US$. The Turkmen money was even smaller. 1 Rial was about 2.50 Turkmen Manat (1 US$ = 25,000 Manat, black market rate, while the inflated government rate 1 US$= 5,200 Manat). With such low value, surprisingly the biggest denomination of the money was only 10,000 Manat, less than half dollar. I changed some pieces of My Rials and got a pile of Turkmen 5,000 Manat banknotes, all with the portrait of the ex-president, Saparmyrat Niyazov, the Turkmenbashi (the father of the Turkmens).

The Iranian border hall was a modern, clean building, resembled waiting halls in airport. It was quite straightforward with minor luggage checking and little interrogation at the passport control. Just a few steps further were already the Turkmen border gate. There was a warm welcome, a warm smile of the Turkmenbashi on a huge poster, to carve on memory of everybody who is coming to Turkmenistan.

“Welcome to Turkmenistan,” said the welcoming banner.

“Independent and Always Neutral Turkmenistan Welcomes You,” said the other in Turkmen language.

The Turkmen border procedure was full of paperworks. First a soldier wrote the detail of the passport before one may enter the immigration hall. Then at the immigration hall, a higher rank immigration officer inputted the information to the computer. A detailed arrival card would be printed on a hologram thick card by a quite modern printing machine. The hologram card was not free though.

“Go to that room,” said the officer pointing a white door on the left side. That was a cashier room.

“12 Dollars, please,” said the woman in that room. She did not wear veil like her sisters in Iran, but a beautiful Turkmen traditional cap.

I handed in the money. 10 dollars for that beautiful hologram card (which was only ‘lent’ to me, as I would have to return it back when I leaved Turkmenistan) and 2 dollars for money exchange receipt.

“Do you have Manat?” asked the lady.

“Yes”

“Can you give me some?” asked the lady again

“How much?”

“Up to you. For me to buy food. For example 20,000 is enough.”

I gave her 5,000. She looked at the money. It was not enough for her. She returned back the money to me, as well as the receipt of the 12$ payment. “No need to give me anything.”

I returned back to the immigration officer. Now I got my passport back, but he pointed me to go to the next room, the doctor’s room. There was a female doctor in white dress, friendly asked about my name, nationality, and age.

“Are you alright? Everything is OK?” she asked in Russian.

“Yes,” I answered, “I don’t have any headache.”

She laughed. “I didn’t ask that. I am not interested about your headache. I am only interested in infection. Infection, you know, infection.”

“I don’t have infection,” I said.

“Yes, I am sure. So, you don’t need to be checked, right?”

“No need.”

She wrote something on the paper, stating that I was healthy, just merely based on the interview and her feeling. She was one of the world’s most efficient doctors.

“Do you have Manat?” she asked the same question as the lady next door.

I placed 10,000 Manat on the table. She was quite happy.

There were not many people crossing to Turkmenistan. It was very difficult to get this country’s visa, and it was not interesting investation destination for most people in neighboring countries. I saw three Iranian businessmen before me and they passed quickly while I was stuck here, now at custom, as I had a huge backpack which the Turkmen guards were more than happy to check thoroughly.

I was asked to show everything I had in my bag. At first they were interested in asking contain of every book I had, but after seeing I had more than 2 dozens of books, they just looked at glance and passed through quickly. They were also happy with my photo albums and asked the stories of every photo, which then made this luggage-search became never-ending chit chat.

At the end, there was too much time wasted, not until half of my rucksack was emptied, they ended the checking.

“No narcotics?”

“No.”

“No opium?”

“No.”

“OK. Just put everything back to your bag.”

Now the declaration form. Everything was written in Russian only. A lady happily filled the form for me. As I told them I needed a copy of the declaration, a younger soldier voluntarily copied the form and gave it to me. While waiting, a higher rank officer kept talking with me. While talking, he spat on the floor. He spat like a machine gun in guerilla war. Each molecule of spit contained huge volume of saliva. Noticing that I was noticing him spitting, he took tissue paper and cleaned the floor by his legs.

The Turkmen guards indeed had a sense of humor hidden somewhere.

It was long, bureaucratic, but not as scary or corrupt as other Central Asian borders.

The next part was going to the capital. It was 30 km away and I was alone. The three Iranian businessmen had already left much earlier and I had nobody to share the cost of the transport. After long bargain with the driver, he agreed at 10$ price. There were a woman and some soldiers sharing the seats with me to the city. All of them worked in this border office and exempted from paying the transport cost.

I arrived in Ashgabat half an hour later.

Rita, the Russian lady in her forties, who was in the same car from the border post, helped me to get into a public city bus.

“How much the bus ticket costs?” I asked Rita.

“50 Manat,” she answered.

“50 thousand manat?” I asked for confirmation, as the Turkmens have habit of eliminating ‘thousand’ when quoting prices.

“No. 50 Manat. Just 50 Manat,” she said. It was even less than 20 Rials (20 Indonesian Rupiah). Even cheap Iranian buses cost 10 times more than this.

She looked contended with my surprise. She happily paid for my bus fare.

“Everything here is free: water, electricity, gas, medical support. Everything is free. We don’t have money, but everything is free, we don’t have the need of big money.”

I asked about her salary and she said it was 75 dollars per month. As she worked at international border post, I thought her salary should be around or higher than the national’s average salary.

“It is not too much,” I said.

“Yes. But don’t forget, everything here is free.”

The new, modern, and comfortable bus passed through huge avenue of Berzengi. White marble high buildings were sparsely distributed along the sides of the smooth highway. Everything looked new and good. Everything looked in order.

“Ashgabat is beautiful city, you see,” said Rita.

“Is it rich?”

She laughed. “Maybe, but we don’t have money. They are rich. We not.”

She laughed again.

I told her about the difficulty of foreigners of getting visa to Turkmenistan.

“I know. I work in border post. It is like a closed country. Not opened yet. Everybody needs visa to come to Turkmenistan. Even it is not easy for Turkmens to travel abroad.”

Rita was Russian descendant. I wondered whether she had Russian passport as well, which would allow her travel more freely in the world.

“No. I only have one passport. Turkmen passport.”

She said she didn’t need to go abroad, as everything was good (and free) already in here. So there was no need to have other passport.

“Will Turkmenistan be more open with the new president?”

“I don’t know,” she smiled, “it was promised. But nothing had changed yet. Maybe we must wait a little bit more time.”

The bus got more crowded. She told me not to say anything more. I know she worried of spies who might listen to our conversation, all in Russian language, the language that is widely spoken and understood here.

I got off in the city center, looking for the house offering for home stay. Ashgabat was not a big capital. One might walk leisurely on its huge avenues, and beautiful new cars racing through the wide roads. Most of the buildings in the center were new and beautiful.

Unlike other ex-Soviet republics, the only visible letters here was Latin alphabet, which was adopted by the Father to codify their Turkmen language, right after the independence. The city was full of slogans. Turkmen language was said to be the oldest form of present-day Turkish language. I could understand little bit of those Turkmen slogans, as I was studying Turkish. “XXI asyry – Turkmening altyn asyrydyr (the 21th century is the golden age of the Turkmens)” said the slogans on many tall ministry buildings. You also could spot everywhere in Ashgabat the national slogan of “Halk, Watan, beyik Turkmenbashy (People, Nation, and Great Turkmenbashi – the Father of the Turkmen, Saparmyrat Niyazov)”, seemed to remind everybody the elements and the reason d’etre of the country. The ‘golden age (altyn asyry)’ was given soul by the spiritual food of Ruhnama (Book of Soul), a life guidebook for the citizens authored by the President Niyazov, the Turkmenbashi, the father of the people. “Ruhnama, Bizing Yolumyzdyr (Rukhnama is Our Way)” and “Turkmening Ruhi Yedigeni (The Spiritual Food of the Turkmens)” said many other slogans. This book of which banners could be seen on every corner of the new city, reminded me to our Indonesian Pancasila, our single ideology which was stuck to our brain after the interpretation of our dictator ex-president, Mr. Soeharto. Reading Ruhnama everyday, said the Turkmen Father when he was alive, would prepare the soul of the Turkmens for the Golden Age (other said it was ticket to heaven).

Turkmenistan was ready for their Golden Age, whether it would come or not.

At the top of a very huge monument at the city center, the Arch of Neutrality, there was a 12m high statue of President Niyazov, polished by gold, revolved to follow the sun’s rotation, heading to the golden-domed palace of the president. The golden statue of Niyazov reminded me to the Altyn Adam, the Golden Man, the warrior statue from 5th century BC formed by 4000 separate gold pieces found near Almaty, Kazakhstan. The Golden Man was then adopted as the symbol of the Golden Future of Kazakhstan, and a glittering replica of it was placed on the top of a high monument in the middle of broad ceremonial square of Respublika Alangy in southern Almaty.

Both of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan were lucky boys among other newly independent Central Asian republics. Both were prospered by unexpected wealth of oil and gas reserves. Both had their own golden men, their own versions of glittering future. With the new wealth, each of them walked through different paths. If Kazakhstan chose the capitalist way, Turkmenistan happily walked through their memory of strong leader and socialism.

At least people showed indifference, like Rita who showed her disapproval of wealth in Kazakhstan, “see, what the use of 500$ income per month if you spend 5$ for each meal. Here is good, everything is free.”

The beautiful image of Ashgabat disappeared immediately when one went further from the main avenues. Here, houses were old, dirty, and messy. Looked like poor housing complex near the Almaty airport area, where once I stayed in. Here, in a housing complex just two blocks from the main avenue and presidential palaces, as well as luxurious marble ministerial buildings and blue-domed parliament house, the ‘golden age’ was at some light years of distance, even though the golden man waving to the sun still made his shadows here, and the clinging sound of the water from giant, glittering marble fountains was still audible.

have you memorize the ruhnama?

Hello Gus,

If oneday you decide to drop by to Turkey, please let me know. Keep my email address; saya tinggal di sana. I’ll be glad to help you anyway I can.