Shakhimardan – An Uzbek Island Surrounded by Kyrgyz Mountains

As artificial as any other thing in Central Asia was the border lines between the countries. The nations created by the Soviet rulers now had to be provided their homeland. Stalin might say, land populated by most Uzbek should be Uzbekistan, those inhabited by mostly Mongoloid Kyrgyz then became Kazakhstan (the Kazakh was called as Kyrgyz) and Kyrgyzstan (of which people was called as Black Kyrgyz). But the matter was not simple in the Ferghana Valley.

Ferghana Valley was always a boiling pot in Central Asia. The people were renowned as deeply religious Muslim, if not fundamentalist. It was more than necessary for the Russian to divide this huge mass with the highest population density all over Central Asia. Then, besides the division of ethnics (who were Uzbek, who were Kyrgyz, and who were Tajik), there was a clever intrigue by dividing the border lands to divide the people. Then, the identity in Ferghana Valley was not single ‘Islam’ anymore, but new artificial entities of Kyrgyz, Uzbek, and Tajik.

But this was not something special if it was just borderlines. Borderlines created by Stalin were so complicated, zigzagging, and nobody understood the reason. In my previous visit to a border area in Ferghana Valley (Gulshan village), the border between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan was in the middle of a kampong road. Houses left of the road was Uzbekistan and right were Kyrgyzstan. All people there were Uzbek ethnic, and those whose house on the right side of the road might be surprised that since then they magically got Kyrgyz passports and had to identify themselves with the Mongoloid Kyrgyz a thousand kilometer away in Bishkek and started to erased their Uzbek past and accept Kyrgyz’s national epoch, the thousand-year-old Manas heroic epoch. It was just 4 m wide kampong road and had decided different fates for people living at different sides of the road. I was not too surprised to know even the border line passed through a family’s family room or kitchen. When you entered the bedroom you were still in Uzbekistan but once you got into your bed you were sleeping in Kyrgyzstan.

S

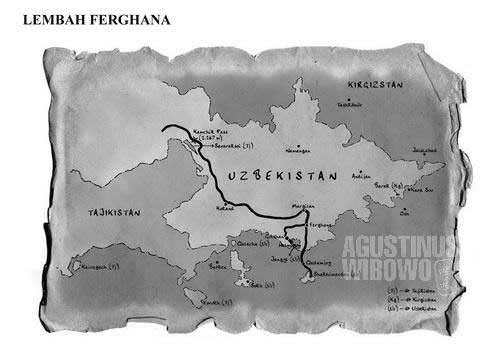

hakhimardan was another story. The gerrymandering border lines didn’t only create weird borders at the middle of kampong road of a homogenous community, but also created tiny enclaves of a republic surrounded by another republic. For Indonesians who don’t know the meaning of ‘enclave’ you should see on map Timor Leste’s Oecussi enclave surrounded by Indonesian East Nusa Tenggara province or Brunei’s eastern and western enclaves surrounded by Malaysia. But Shakhimardan, as well as dozens of other enclaves in this area, were too tiny to even make their way to regional map. Some quite sizable enclaves in Ferghana Valley included Shahkhimardan, Sokh, and Vorukh. Vorukh is Tajikistan territory completely surrounded by Kyrgyzstan. Sokh is, despite of being Uzbekistan territory surrounded by Kyrgyzstan, populated by Tajik ethnic. Sokh had been a major focus in Uzbekistan as this enclave had been the hiding place of the leaders of Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (Harakatul Islami Uzbekistan), a group declared as terrorist group by Uzbek president, Islom Karimov.

The existence of enclaves like this, or an ‘island’ of a republic surrounded by other republic, was indeed seeds planted by the Soviet regime so that each republic was heavily linked and relied to others, to dilute the independent tendencies of the republics. National identities were spread so people start to think, ‘I am not part of them, and they are not part of us.’ It worked, even until the breakdown of Soviet Union, the Soviet ghost still didn’t fade away. When the Uzbek president declared to crackdown the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) until it roots, it was important for the President to conduct a military operation to Sokh. But to do that, the armies of Uzbekistan had to pass Kyrgyz territory.

We might not see the border. But for the locals, it is very clear which mountain is Kyrgyzstan’s, which field is Uzbekistan’s

As the big brother in Central Asia, Uzbekistan was known to press other neighboring countries to listen to its policies. Uzbek government successfully lobbied the Kyrgyz government to provide the road from Uzbek ‘mainland’ to Sokh so that the Uzbek armies could reach the problematic area legally. This movement caused anger far in Bishkek. Nationalist Kyrgyz protested in the capital, as if they handed the road for the Uzbek, then it turned to create a Kyrgyz enclave surrounded by Uzbek territory, and it was dangerous as well for Kyrgyz national security.

Considering to its location, being an enclave in Kyrgyz territory and very near to Tajikistan – Uzbekistan’s regional rival, Sokh became a safe hiding place for the forbidden fundamentalist movement. IMU and Hizbut Tahir leaders used Sokh, Batken, and Tajikistan’s Garm Valleys as their safe base camps, and the angered Uzbek president blamed Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan of being not cooperative in ‘war against terrorism’. The relationship between Central Asian countries was very uneasy, and Sokh, an enclave created by the Soviet rule with even unknown reason why it should be part of Uzbekistan despite of Tajik population, was one of the problem makers.

Shakhimardan was not as problematic and sensitive area as Sokh. In fact, it was among favorite tourist destinations in Uzbekistan, despite of its difficult-to-reach location. It is located 25 km south of Uzbekistan ‘mainland’, surrounded by high mountains of Kyrgyzstan. The last frontier of Uzbekistan is the town of Vadil, where a friend of mine, Sardor, invited me to stay. Sardor is a student of Arabic language in Tashkent but he spoke Farsi as well.

I always wanted to visit Shakhimardan since my first visit in 2004. I remembered a man from Shakhimardan in Ferghana offered to smuggle me there in a taxi as he claimed ‘he knew everybody at the borders’. But I had very limited time so I refused him. This year I was very happy that Sardor invited me to his house in Vadil and promised me that he would try the best to at least let me see the beautiful Shakhimardan.

For Uzbek, going to Shakhimardan was a matter of passport (Uzbek citizens only had passports in place of ID cards) checking. But for a foreigner like me, going to Shakhimardan means I should have a Kyrgyz visa to enter Kyrgyz territory and another Uzbek visa to reenter Uzbekistan territory. For sure, I didn’t possess and I didn’t intend to possess any of these unnecessarily expensive documentations. For Sardor, it was indeed a headache as well.

To go to Shakhimardan, one needed to exit Uzbek territory, enter Kyrgyz territory, pass through Kyrgyz town of Qadamjoy, exit Kyrgyz territory, and enter Uzbek territory of Shakhimardan. To go back to Ferghana, then it was the same procedure at reverse. This means one should pass 8 border checks to go to Shakhimardan and return. Even if you tried to smuggle, it was very difficult to assure that you could pass all of these 8 checks without being known.

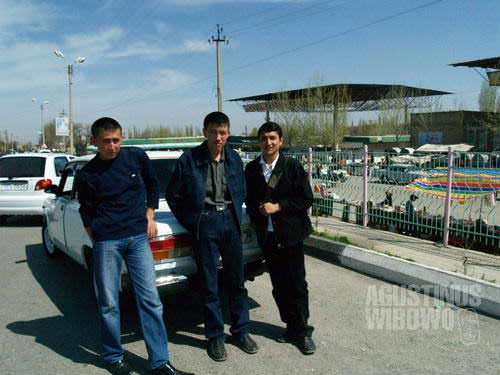

As anywhere else in Central Asia, a taxi driver is a respected job. Luckily, Sardor knew many taxi drivers from his neighborhood, and he negotiated how to smuggle me to Shakhimardan to many of his driver friends in the bus station. Most of them were not dare to attempt. But we learned that the problems usually came from the Uzbek border guards as the Kyrgyz are usually very laid back. And don’t forget, I had a Kyrgyz face.

Finding a taxi in Ferghana willing to take me—a foreigner illegal visitor—to Shakhimardan is actually not an easy job

Bakhtiyor Aka (aka in Uzbek means big brother) was one of the drivers and happened to be Sardor’s neighbor. He said he could be trusted to bring me to Shakhimardan safely, as he knew many people from the border. But his price was expensive. To go and back he quoted 40000 Sum (about 35 dollars). With neighbor relationship, we succeeded to bring it down to 20000 Sum.

What made Bakhtiyor Aka different from others was, despite of being Uzbek citizen, his car had a Kyrgyz plate number. It meant he didn’t need to stop his car even once when passing through Kyrgyz border guards. But Uzbek border guards always wanted to check everything. Being an Uzbek citizen meant it wouldn’t be problem for him (for him, not for me).

The first gate we had to pass was Uzbek border. Of course this was the first problem we face, as Bakhtiyor Aka had to have his car checked. But he was experienced with this. He let us wait inside the car when he negotiated a talk with a Kyrgyz driver.

This was the situation at the border. A road stretched from Vadil to Qadamjoy, where the two border securities of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan located. Another road, parallel to this one, is located completely in Kyrgyz territory where no border check was necessary. This road connected Qadamjoy to Kyrgyz city of Osh. These two roads were close each other. At the point where I was standing, 20 m from the Uzbek border post, the Kyrgyz road is just located 5 m away parallel to this road, separated by a line of barriers but pedestrians can easily cross.

From the space between barriers, I went to Kyrgyz territory. The situation in the border area was very messy and pedestrians walked through these barriers between Uzbek and Kyrgyz road freely. There a Kyrgyz driver whom Bahtiyor Aka negotiated with had been waiting for us, and let us to get in his car, which had completely dark mirror.

Now, I was inside a Kyrgyz car inside Kyrgyz territory, on a Kyrgyz road parallel to an Uzbek road which then met together at the end of the border posts. During the way I could see both of Uzbek and Kyrgyz border posts without being stopped at all, as being in Kyrgyz road we didn’t need any border check. Both of the border posts were small, but Uzbek border posts looked more rigid. There was quarantine check and the “blue-white-green”, the colors of Uzbek flag, dominated buildings of Uzbek frontier changed to be red-dominated Kyrgyz frontier. Kyrgyz flag was red dominated.

These two parallel roads meet at the end of the Kyrgyz post. We waited Bakhtiyor Aka here. After waiting about 10 minutes, Bakhtiyor Aka came out and we had to move back to his car. Then the two drivers negotiated the price. For just a 100 m drive, Bakhtiyor Aka had to pay that Kyrgyz driver 8000 Sum (about 6$). I safely entered Kyrgyz territory, and now the Kyrgyz story started.

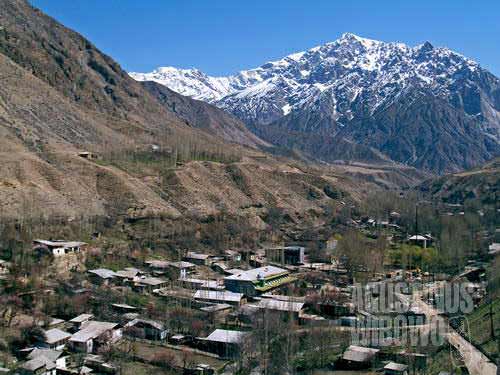

The image of Kyrgyz land was always high land surrounded by snowcapped mountains. The road was full of slogans in Cyrillic character. Kyrgyzstan, unlike Uzbekistan with its full commitment to replace the Cyrillic character at least before 2008, was very laid back in allowing its national language to be written in that Soviet alphabet. Since its independence, only car plate number was changed to Latin alphabet. Everything else was still in Kyrgyz Cyrillic. It was very uncertain whether the commitment of having Latinized Kyrgyz would be complied.

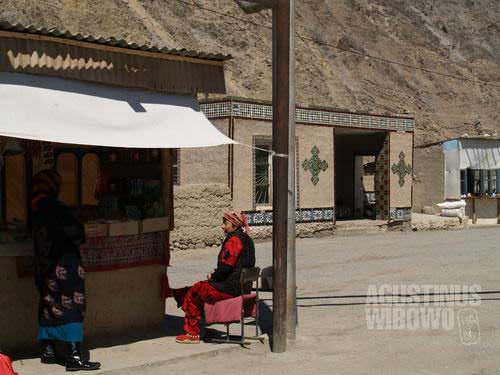

The town of Qadamjoy started soon. The Kyrgyz town didn’t differ so much from Uzbek’s Vodil, but the existence of Mongoloid Kyrgyz face under Kyrgyz national cap, ak kalpak, reminded that this was territory of Kyrgyzstan. Slogans in Kyrgyz language, Kyrgyz flag, boards about a happy Kyrgyz family, and a cemetery were signs to remind that this area was linked to Bishkek. The cemetery, near the police station, had very patriotic Russian slogan on the wall: Nikto Ne Zabiraet, Nichego Ne Zabiratsya (Nobody will Forget, Nothing will be Forgotten).

Despite of having a huge proportion of Uzbek ethnic population, Qadamjoy also had a noticeable Kyrgyz ethnic. Uzbek ethnic was indeed spread all over the valley, and in all neighboring countries, Uzbek was always a strong minority. The opposite logic didn’t work. Even in Vodil, Kyrgyz ethnic was extinct.

Ferghana Valley was always the most religious area all over Central Asia. I noticed people in Uzbek side of the valley always reminded me to deliver my prayers, and here, in Qadamjoy, I spotted little Kyrgyz boys wearing white turbans. Kyrgyz was known as quite secular, as Islam might not suit well with nomadic tradition. But in Ferghana Valley, where people used to be sedentary since centuries ago, the local and Islamic tradition went along and created strongly religious communities, no matter whether they were Uzbek, Tajik, or Kyrgyz.

Kyrgyzstan is exporter of electricity. The availability of electric infrastructure is an obvious sight of Kyrgyzstan, including the small village of Qadamjoy

There was also a sacred mausoleum in Qadamjoy. The entrance gate resembled skeleton of a Kyrgyz yurt, and bear the coat-of-arms of Kyrgyzstan: roof of traditional Kyrgyz yurt. Bakhtiyar Aka asked me to go down and pray for my safety in this Kyrgyz territory. But he warned me, “Don’t get too close. There are too many Kyrgyz here. Very dangerous!”

The Kyrgyz bazaar was very crowded. I realized how this border lines made everything difficult. For even simple local trade, people from previously neighboring villages now had to cross international borders. Water, irrigation, electricity, mobile signals, power systems, education systems were all divided by these borders. (But my Uzbek SIM Card worked properly in Qadamjoy – Kyrgyz territory, but there was no signal at all after reaching Shakhimardan – Uzbek territory). Children were separated from their schools because they possessed different nationality, which was decided on which sides of the border their homes were.

The blue sky seems like a borderless world. But in fact, the national borderlines are extended vertically from land to the sky.

At least Uzbek-Kyrgyz relationship was not as bad as Uzbek-Tajik relationship. Uzbekistan and Tajikistan required visa for border crossings of both nationals. The visa requirement between Uzbek and Kyrgyz was just abolished but crook officials were still notorious of extorting money from the villagers. I bet this Qadamjoy market should be much livelier compared to Tajikistan border towns, as Qadamjoy enjoyed relatively easy access to Ferghana in Uzbekistan.

The road went through beautiful winding road up to Shakhimardan. We didn’t find any difficulty at all exiting the Kyrgyz border. Our car was not stopped and Bakhtiyor Aka just drove through the Kyrgyz border guards who let him pass. It was because we were in a car with Kyrgyz plate number.

The Uzbek frontier to Shakhimardan, said Bakhtiyor, was the most difficult post in this journey. Bakhtiyor went off and negotiated with a young border guard. Sardor, beside me, kept murmuring a prayer. I knew he was scared. I knew this part was not easy.

Then the border guard, a young man who actually also had to pass his compulsory military service, asked Sardor to went off and showed his document. A compromise had been reached. This young guard allowed me, an Indonesian, to pass freely to Shakhimardan to perform my pilgrimage.

Yes, we got permission for a pilgrimage. Assuming that Indonesians were devout Muslim, this guard agreed to help us without asking any bribe. But we had to return back to the border at most 45 minutes of time, because due to work shift, he would be replaced by other men after 45 minutes and we could be punished of entering illegally.

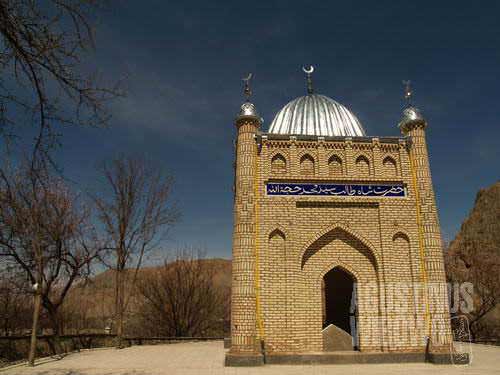

I mentioned about pilgrimage. Shakhimardan was an alpine valley where it was believed as the resting place of Ali bin Abu Thalib, cousin-cum-son-in-law of Prophet Muhammad, the Fourth Caliph as well as the First Imam of the Shiites. Well…, there was not only Shakhimardan claiming this. Mazar Sharif in northern Afghanistan also had the same claim, and in the 12th century a magnificent mausoleum was built there. At least there were 7 places in Asia and Middle East claiming the same. I have learnt that the corpse of Ali was put on a donkey by his followers to prevent it being destroyed by the Caliphate enemies. The donkey then wandered to unknown direction and in fact nobody really knew where the donkey stopped and the corpse of Ali was properly rested. This caused the claims of different places as the resting place of Ali.

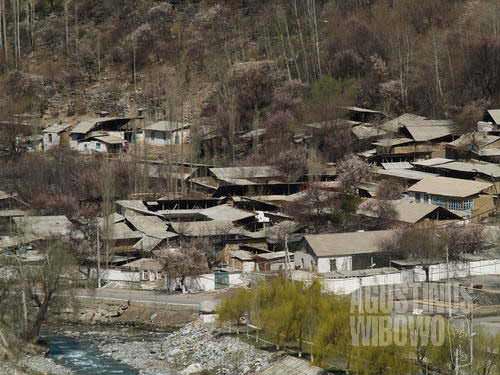

Desserted houses of Shakhimardan. This area will be lively again when summer months arrive and pilgrims come.

Little mosque and mausoleum for Ali was built at the top of a hill of Shakhimardan, from where one could see the beautiful aerial view of the valley. The Communist rulers had destroyed the original mosque (they claimed the burning was done by the Muslim guerilla fighters known as basmachi). The little Ali shrine here actually was built after the independence of Uzbekistan, in front of the deserted museum, and it started the pilgrim waves again here.

The caretaker brought me inside and we delivered prayers, as most of other pilgrims did. Sardor was excited as well, and he was also half-believed, half-not-believed, that Ali’s body was buried here. The old caretakers were also delighted to hear about Mazar e Sharif. And he proposed an idea, that as a holy man, it was possible that Ali’s body could exist in different places at the same time. I remembered a Sufi from Makassar (Celebes, Indonesia) who brought Islam to South Africa had tombs both in South Africa and in Indonesia. As Ali was much more important in Muslim world, so it was possible that his body could be in 7 different holy places.

Shakhimardan was quite deserted. Most of the houses were empty. It was not holiday season yet, and the people who had houses here prefer to stay in Uzbekistan mainland rather than in this ‘island’ surrounded by foreign Kyrgyzstan. Considering the difficulties of being isolated here, it was understandable. The bazaar of Shakhimardan was very pitiful at this time of the year. If a truck full of trading goods had to pass 8 international borders you could imagine how much money would evaporate to smooth the road. And at this moment, Shakhimardan was not profitable. Pilgrim season had not started yet. Tourist money was not enough to cover the cost of the bureaucracy.

You can imagine when Uzbekistan relation with other neighboring countries getting worse. All of the enclaves would be completely cut from outside world. Isolated. Accessing Shakhimardan was very difficult when Uzbek-Kyrgyz relation heatened up. Tajik enclaves in Uzbekistan’s Ferghana Valley were also difficult to reach. Sokh remained a sensitive area and access was still very difficult for most people. You could imagine if your little kampong was isolated for months, and even when you wanted to put sugar to your tea, you would have to pray God for miracles.

Near the bazaar there was a small lovely mosque. Sardor claimed it was the most beautiful mosque in Uzbekistan. The caretaker of the mosque was a bearded man. It was actually scarce now to see young or middle aged men in Uzbekistan with beard. It was a sensitive issue, of course, but after the Uzbek government decided to crack down the fundamentalist movements in the valley, even being bearded already caused enough harassment from the military. Nowadays it was very rare to see men with beard, as somehow Uzbekistan government successfully linked ‘beard’ to ‘terrorism’.

Returning back to Ferghana was repeating the whole border-crossing procedure. The same young Uzbek soldier still guarded the border post. We thanked him a lot for his cooperation, and he was happy to help us. Entering Kyrgyzstan was not a problem at all with Bakhtiyor’s Kyrgyz car, which then I found he bought illegally as he was Uzbek citizen.

The problem rose again when we tried to enter the Uzbek mainland. We had to take the same parallel road to avoid the border posts, while Bakhtiyor’s car had to pass this road to return to Vodil. He flagged down a Kyrgyz taxi with a Kyrgyz driver, and he negotiated everything for us.

This Kyrgyz taxi driver, before we went into his car, interrogated us little bit.

“No drugs? No narcotics?”

“No,” Sardor answered.

“No terrorist?” he asked again.

“No.”

“Then why you have to go this way?” the driver was curious.

“Because we don’t have documents.”

“OK. Let’s go.”

Having no documents is much a smaller sin compared to having drugs or being a terrorist. Luckily we didnt have beards as well. It seemed that he used to transport illegal border crossers like this, and this was his source of income.

We passed again the Kyrgyz border post, and suddenly those Cyrillic letters turned to be Latinized character after we passed the green-white-blue buildings of Uzbek post. Welcome to Uzbekistan.

Oooops, that Uzbekistan started at the other side of the road. Now we were still in the parallel road in the Kyrgyz world. The car dumped us near a cemetery. This parallel road went straight to Osh, but this cemetery was the backdoor to Uzbekistan’s backyard.

We had to pretend now, as an Uzbek visiting the cemetery. Otherwise if any Uzbek or Kyrgyz police spotted us using this cemetery for border crossing, we would be in trouble. Sardor’s little brother was buried here, as well as his grandmother. We offered prayers there. And we continued our journey, to Uzbekistan.

Just after the cemetery finished, we entered a small wooden gate, and arrived at a backyard of a house. This house was used as mahalla, or a place for community meeting. Reaching this house, we came back to normal life in Uzbek mainland.

Menarik cerita dari Mas Agus tentang petualangan di berbagai negeri Asia. salut buat Mas Agus, tolong jangan lupakan kota Pisang Lumajang-nya yakh. kalau di Uzbekistan Hizbut-tahrir di larang bahkan dianggap teroris di Indonesia justru mulai diperhitungkan sebagai ormas islam yang melakukan dakwah dengan pemikiran tanpa kekerasan. kalau ingat perjalanan mas Agus bagus juga yakh kalau jadi da’i penyebar damai dan rahmat islam ke seluruh dunia yang dulu dilakukan oleh para pendulu islam seperti wali songo di jawa yang aslinya mereka bukan orang jawa.