Thar Desert – Life of Survival

May 22, 2006

Special thanks to Om Parkash Piragani from Sami Samaj Sujag Sangat and Jamal from Ramsar

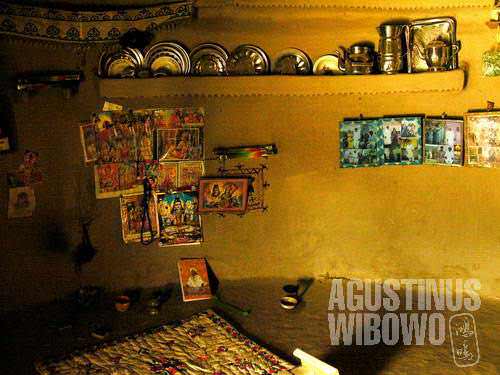

Otagh

It’s a vast, hot, dry, dusty, shady desert area stretching from the corner of Interior Sindh of Pakistan up till Rajasthan and Gujarat over the other side there in India. Water is a main problem here, food is insufficient, and education is luxury. Thar or Tharparkar desert is where about one and half million tribal people, living in more than 800 widespread villages, survives their life, with their cattle, despite all of the hardship.

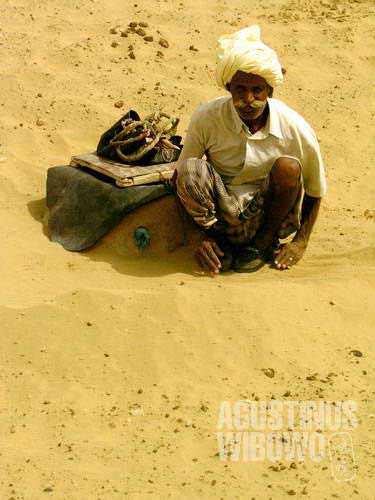

Umerkot is a small, busy town connecting the desert to the interior Pakistan. It’s a vital survival for the people from the deep desert. Umerkot is not a common Pakistani city. It boasts the point of world history as the birth place of the biggest Mughal king, Akbar. And what makes the town special: it has the largest Hindu inhabitants proportion in this Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Most of the people, some claimed seventy percent, are Hindus. If might said, Umerkot is the ‘little India’ of Pakistan. The town has some offices, a bustling bazaar, rows of shops, and decent schools. For the people in the desert, Umerkot, as other little towns surrounding the desert, is source of life. As the desert now can not provide food to sustain the life (after years of drought), the bazaar of Umerkot with flourishing fruits and vegetables is crucial. It’s also where the uneducated tribal people get money from: they work as labour, they sell their frustratingly thin and unhealthy cattle, or they beg for money here.

Difficult journey

Many parts of the desert are now reachable by public transport. The government has built quite good road infrastructure to connect some big villages in the deep desert to outside world. Even the remote Naga Pakar and Indian border of Kokhrophar are now accessible by public bus. The buses are mostly very old, but it provides cheap transport for the villagers. There are several buses serving many different routes, waiting for passengers in the bus terminal of Umerkot everyday. The schedule of departure and arrival is very limited, and suited to the villagers needs. The bus usually departs early morning from the deep desert bringing all of the villagers who are going to town to shop or to trade, wait until the afternoon in the town, and go back with almost the same passengers, happy to go home, back to the deep desert.

I was in a busy and crowded old bus, going to Ramsar, a village in the interior of Thar Desert, with Jamal who was going to take me to his home village. Jamal is a teacher, and just attended social worker training provided by the Sami Samaj Sujag Sangat organization in Umerkot. The bus was full of people. Women passengers got special place at the middle part of the bus, everyone got a seat. The male passengers were squinched together in some rows of seat behind the driver and at the end of the bus, together with sacks of materials and vegetables they bought from the bazaar, and also live chicken. People in rural areas of Pakistan prefer to buy live chicken rather than chicken meat, so that they may enjoy fresh chicken meat at any time they want. But it also turned the house to be a small ‘poultry farm’. Jamal knew that I was suffering from my sickness, that he even borrowed a cooler to keep the water and ice cold, so that I may keep drinking cold water during my stay in the hot desert. It was unnecessary though.

Ramsar

Ramsar is located 25 km away from Umerkot, and it took about 75 minutes to reach. The bus actually goes further until Mithi, a small town in the deep desert. It seems that the ticket seller knows everybody in his bus, that he didn’t need to ask for destination when collecting tickets. The ticket price also depends on the distance. For the 25 km distance, Jamal had to pay 25 Rs. The journey was not always easy. The smooth sand from the desert is easily transported by the wind to cover the main road. And this old bus is not a jeep. It can not pass through the sand. And it comes the turn of the passengers to do a little bit labour, to make the path for the bus by removing the sand with everything possible: shovel, wood, and even palms of their hands. It reminded me to bus journey up north there in the mountainous areas of Pakistan, where the passengers has to do work together to remove the stones that blocked their way, brought by landslides after rain shower. But here is another world in the same country.

Vast and dry

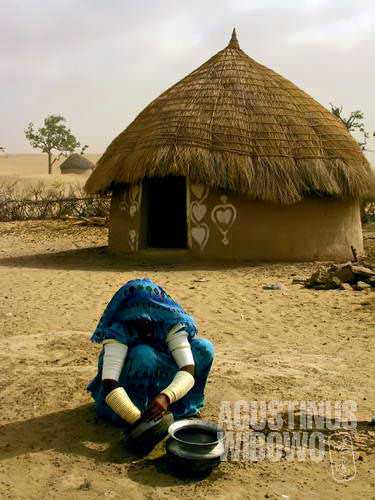

Ramsar is quite a sizeable village in Thar desert. It is home of almost 2,000 people, from about 150 families, Hindus and Muslims. The people of these two religions live separately. The Muslim village of Ramsar, of about 50 families, live close to the main road, while the Hindu one is 1.5 km away behind the sand hills after the Muslim village. Jamal is a Muslim, and today I was invited to the ‘otagh’ or guest room of the village. The houses in the Thar desert have unique architecture. They call it as ‘chowra’. The shape is mostly circular, with high roof from desert grass. The rooms are highly ventilated. The guest room is a special chowra, with huger size and some charpoys for the people to sit and sleep. It has door, and never been closed. The windows are also mere holes for the wind to pass through, also cannot be closed. The main function of otagh is a place for guests coming to the village. Otagh also functions as community halls where the males of the villages sit together and chat.

Jamal is a teacher. He teaches in his village, and he has 15 students. All his relatives. In fact all people in the same village are connected by blood relation. He gets payment from the government, and he also owns a shop in the village which sells daily needs. He doesn’t need to go to Umerkot everyday to get his commodity. Delivery order by phone makes it. You might be surprised that people in such villages without even water and electricity are so attached to the phone. So is Jamal. He is always with his phone next to him. The recent technology from China allows the villagers to get wireless phone with Umerkot number, and the area scope of these wireless phones is up till 25 kilometres. Usually people with business like Jamal own wireless phone like this, which is also another source of income for him, as the phone also serves as PCO (Public Call Office = public telephone) for other villagers.

The lonely desert

About life in the desert, Jamal recounted to me when we were enjoying afternoon on the charpoys outside the otagh. People in desert area likes to sit outside the house to enjoy the cool afternoon, and most of them also sleep outside as the temperature goes down very pleasantly at night. But the wind was tremendous, it also brings the sand together that people may be full after eating some kilograms of sands. But sands are daily food for desert people. His little boy, Ghulam Qadeer, two years old, just started to walk, and enjoys to be swung to the sky by his father. He laughed loudly when he flied to the sky.

“Life here is so difficult,” said Jamal, “there is no water for us, no food for our animals, no milk for our children because the cows are so weak, and there was no rain for years.”

Drought had come to this desert since four years ago, said Jamal. The rainy season is supposed to be in June until August, where there should be around three or four times of rain. Jamal said that no rain came at all in last four years. Other villagers told me that rain came every year but the quantity of water was too low.

“But you should see when rain comes here… this dry desert would turn into green plain… and our Thar becomes like Kashmir,” said Jamal. He has never been to Kashmir, but I believe his description that desert can be zipped into a jungle just in overnight after a rain.

Walking on hot sand for hours, just for water

Jamal speaks Urdu. He teaches Sindhi, the local language of the province, in his school. In fact he has to teach all subjects. Most people in Ramsar speaks Urdu, so I could communicate with them easily. But this is not majority of villages in the deep desert, where education has not touched them, tribal people only speaks their local desert language: Mawari. They call the deep desert, the vast dry sand hills around their village as ‘jungle’. The English word ‘jungle’ comes from Urdu ‘jangal’. But the ‘jungle’ these people of Ramsar are living now is a yellow jungle with only sand and bushes.

Monsoon is the long awaited season in the desert. The long awaited rain never comes, but snakes never absent in their season: from August until November. The cool weather after monsoon is also the season of weddings. “You should see our tradition of wedding,” said Jamal, “when we all dance and sing.” The marriage is always intra-village, which means that both bride and groom actually still have blood link, which is common practise in Pakistan, as most marriages are arranged marriages decided by parents of both sides. The bride would be also under purdah, so that nobody could see her. But considering that the whole village is of a same clan, it seemed that purdah was not that necessary here. The purdah is just a sheet covering the bride face, just to fulfil the requirements of the religion.

I could not stand the strong wind outside, as it brought too much sand to my stomach. I chose to bring my charpoy back to otagh and stayed inside. When the night falls, the desert turned to be dark, and the sky was dotted by millions of winkling stars. Electricity never comes here. Light only came from the small oil lamp which Jamal brought. It was also special for me. Most people even don’t bother with this kind of lamp, as they own very tiny torch purchased from Umerkot.

“Son, study hard, then be a minister, and bring electricity to your village…”

Boys from the village were happy seeing a stranger coming to their village. And everybody was sitting around the beds in the otagh. But when dinner time came, everybody went home to their own huts. It was Muhammad Rahim, Jamal’s four year old nephew, left there and made sketch on the dust floor with his finger. His father said full of hope, “Beta, kitaab parho, vazir ho jao, apne gaon me bizli lagao… (son, study hard, then you be a minister, and bring electricity to your own village…) ” The deep desert also produces big men. In Karachi there is a minister in the government of Sindh who was from Mithi. And people from Tharparkar put tons of hopes on him. Still, villages like Ramsar had to suffer some more decades before development really reaches them.

For dinner, Jamal brought rice and fried tomato to my room. As commonly in Sub continent, people rarely eats on table. They eat either on the floor or on the bed. And my charpoy turned to be a dining table after a sheet was put on it to prevent the food falls to the bed. With the sand coming together with the wind passing through the highly ventilated otagh, food was full of sand. And so was the mouth. As said before, sand is the staple food for people here. Jamal said that the tomato and rice was also special for me. For daily food they rarely go further than chapatti and dhal (lentils).

The oil lamp winkling in the dark desert attracted many little bugs and insects to the otagh. The bugs were black with strong skin, and the ants may be as big as your palm. There were many other unrecognizable insects coming to the hut. And not only these little creatures, the goats also made their way here to find something eatable on the floor. I slept with worry of being bitten by the insects and being licked by the goat, and accompanied by the cry of the sheep in the room. But I slept very soundly.

The morning started when the Imam of the village chant the azan (prayer call) from the little mosque built from mud. It was 5:30 am and it was still dark outside. The azan was delivered orally, without the noisy loudspeaker. Here, prayer calls are peaceful time of pacification. Not all males go to pray. They are less religious here as food is still the biggest problem. The daily activities of the village start by then.

Behind curtain

They are not on diet

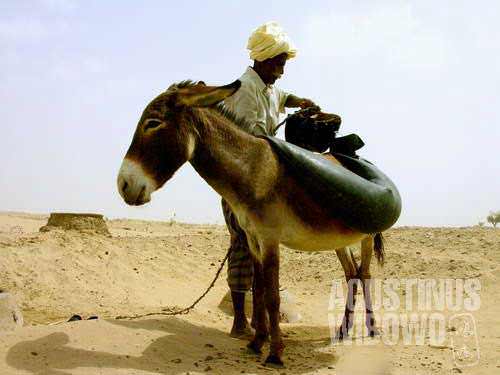

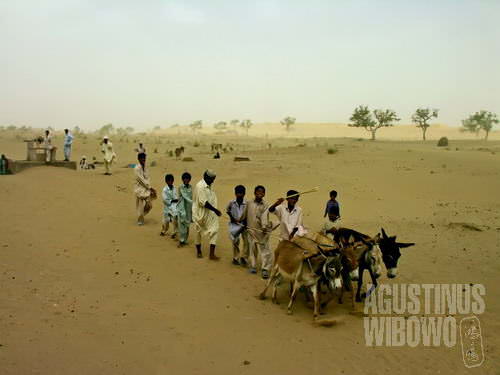

Old woman in the neighbourhood feeds the cattle with wheat extract (bought from Umerkot) which was mixed and pressed with water. The donkeys and camels like it very much. They are extremely skinny. Then it is turn for the boys and girls to bring the goats and cows to the grassland. The ‘cowboy’ sits on his donkey, navigating his cattle. The donkey and camel also serve as water collector. The people put rubber skin water gallon on the animals, then walked for a kilometre where the family water storage is located, put some kilograms of water for the day use, and go home. Some NGOs and government institutions has built water storage near the community, so the villagers don’t need to walk far to collect water everyday. Before they had to go far away to the well, dig the water, and walk back the distance of some kilometres, everyday. Now life is little bit easier. The cows are there to provide milk. But they are too skinny that now the village children have no milk to drink. So are the goats. The Muslims also eat the beef, as their cows hardly sell in the town.

Source of creation

Jamal was taking shower with bucket water. He used only two small buckets of water for his morning rituals. He said that he had shower every day. Water is in crisis now. Sometimes he had shower after two days, and the children even get less frequency. They look very dirty as they play a lot in the ‘jungle’ and rarely shower.

There was a pile of sunflower seeds next to the otagh. People from the village managed to order a truck of sunflower seeds and today is the day of distribution. Some Hindu men from the Hindu village also came to get their portion. They use a traditional way of weighing the seeds. These seeds are also from Umerkot, and are good for the animals. The villagers pay 120 Rs for 40 kg of the sunflower seed. It last not longer than three days. It does cost a lot for raising the cattle here, and I doubt that their animal might be sold easily in the town, considering that they were all lack of nutrition. A goat might be sold up to 3000 Rupees in Umerkot. But the competition is harsh there.

Picking and eating sunflower seeds from the sand

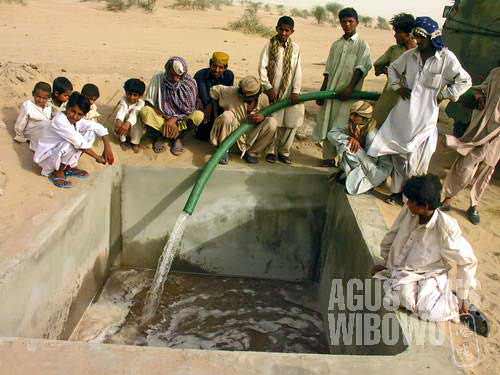

Water gathering is a big business here

They have to walk for kilometers just to get water

And they treat water as precious treasures

There was no issue between the Muslims and the Hindus, even they live separately. The interaction between the two villages is frequent, and fighting almost never happened. Some Hindu men come often to the Muslim village and they work and discuss life problems with their counterparts. The Hindu Ramsar village is separated by sand hills from the Muslim Ramsar. They have their own school, their own water well and storage, their own shops, their own systems, … in a word, they are in separated village but with the same name.

I went to the Hindu village with Anwar, also a teacher but works in a village five kilometres away. He is Muslim, but he knows some friends in the Hindu village. Anwar earns 3000 Rs per month as a teacher, and he goes to his working place by the public bus (the only bus operating was that one connecting Umerkot and Mithi). The bus fare is free for him.

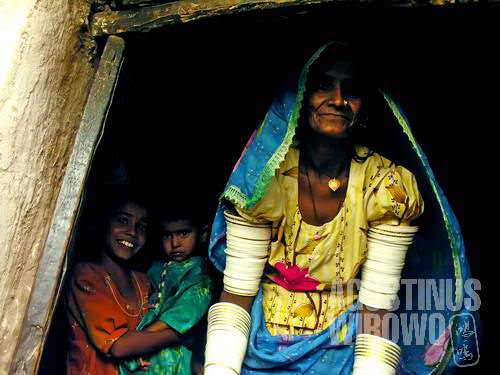

In the Hindu village, I was guided by Jaglo, a doctor. As being a doctor, he is very famous in Ramsar, and people called him as ‘doctor sahab’. He is a man of thirty something, with round face and round body, and is very friendly. All Hindus in the desert were from the lowest caste of their religions, the Sudras. They also had been target of conversion of Korean Christian missionaries who sometime comes to Umerkot.

Shop

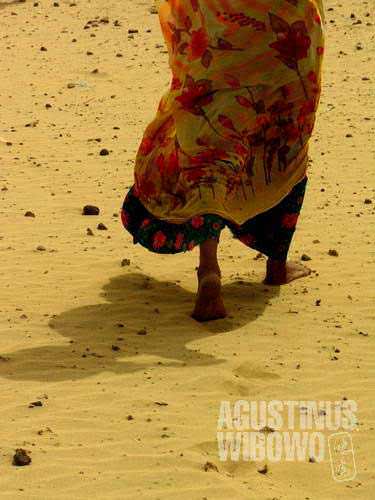

Woman from a Hindu village

The Hindu village looks quite identical with the Muslim one. But the Hindus also decorated the house with white painting on the house. Some has floral motive, some others has animal painting. The interior of the house looks like the otagh where I sleep. Empty. There was only some beds, some dinning plates, pictures of ancestors and gods on wall, and that’s all. People are too poor, they have nothing to purchase. Primary needs can be fulfilled in traditional ways they used to live for thousands of years. And secondary goods are also of no use here, as there is no electricity at all.

One example of the traditional way of survival is the cattle shit. Women and children collect the shit of their cows, put it in bucket, then dry it near the house. They use the dried shits to make fire. The other use is as air refresher inside the house. The people spread the shits on the floor as they like the smell of it, and thus, it’s a traditional air refresher. Shits also can be used as medicine, in Ayurvedic way. If a woman has difficulty when bearing her baby, then she should drink a glass of water mixed with the shit, and the baby will come out easily.

Gathering to get water

The clothings also have social meanings

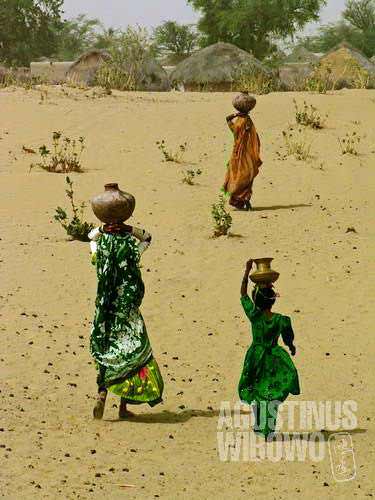

The kitchen is usually in separate chowra, when they can afford. It’s usually the ladies who prepare the food. Sometimes it seems that ladies do really work harder than males here. They collect water in the hot daytime by walking with their water pots, they feed the animals, they collect water from the water storage near the house, they cook the food for the family, they clean the house… and they do the same work even during pregnancy. Awareness of pregnancy health is very low in the villages. And most of the ladies are illiterate. The females in the desert always wear colourful dress. The Hindu women wear choli or polka combined with gaghra or lengga(shirt and long skirt) but the Muslims stick to the shalwar qameez. Well to do women wear beautifully embroidered dress. The head is usually covered by chunri or poti, the colourful shawl which also served as purdah for the Muslims. Most Hindus and some Muslims still stick to the desert tradition of wearing chura, or the bangles on their arms. When the upper arms and lower arms were covered fully by the bangles, it means that this woman is married. Girls usually wear about a dozen bangles to cover their lower arms. It also served as accessory.

Donkeys working hours

They never forget to pray to their Gods

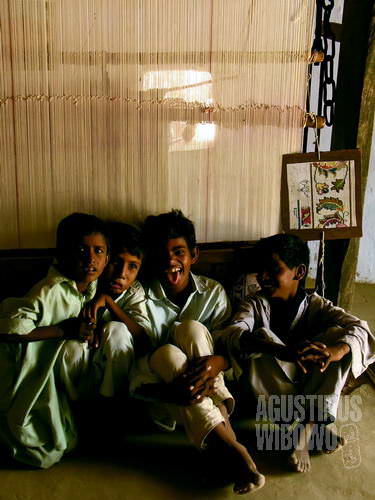

Every family at least has a carpet weaving machine in their home. The men and young girls make the carpet when they have free time. The design is quite complex. I have learnt that the selling price of a carpet is at least 6000 Rupees, and it needs a month for two people to work on a carpet. The carpet making is a desert tradition, but not all people know it. The knowledge of carpet making came to Ramsar just 25 years ago. Some NGOs, like Sami Samaj Sujag Sangat, has training centre for the villagers to learn to make carpet. It is a huge income resource if they work hard. The material of a carpet cost 3000 Rs, so for their labour they earn 3000 Rs net. It is a reliable income, compared to selling skinny cattle in bazaar. In Ramsar, only Hindu village has the carpet making tradition. The Muslim part does not.

Collecting animal shits

Water collecting is a big business here. Near this Hindu village, a water pump was built by a foreign organization. Everyday, started at 11 when the day also starts to be hot, people collect water. As water is scarce, there is numbering order of who should collect water at what time. Women start walk from their village with the water pots on their head. Some old ladies even didn’t wear shoes to walk on the burning sand. The water pump is a kilometre away. The water is very deep in the well. There were four donkeys, connected to a bucket which could carry 25 kg of water, to pull out the water from the well. The donkeys were navigated by a boy, who pushed them to walk around 100 meters to pull the bucket out. Then it turns for the people waiting around the well to distribute the water. The women put the water to the pots and carry them on their heads. Some other men put directly to his water storage nearby for his further use, and the others load it onto their donkey. Water is priceless here. The water storage buried inside the sand has even padlock to prevent people of stealing water. Has the water here even dried? The well might have few water after a session of pumping, but an hour or two later water will come again so that the next shift of people will be assured to get water. But in this hot summer the need of water is enormous, that the well never completely fulfils the needs of the villagers.

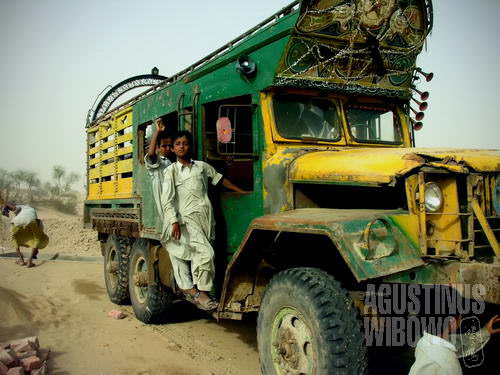

Kekra, vehicle of the desert

Other than collecting waters and feeding the animals, there are not many other things to be done in the village. Men start to pass their time by chatting, as agriculture is no more existent since the drought. Passing time, waiting, watching the wind passing transporting the smooth sand.

Waiting for hopes, waiting for someone who will come to change their future, that is the only thing children here spend their days for. Under the hot sun they play the traditional Sindhi game or wrestling, or otherwise force the animals to do the wrestling. Insects and goats are favourite fighting animals. Children also came around the sunflower seed weighing area, and pick some seeds on the ground, and eat it (supposed to be food of their animals). Waiting for hope is best described when a vehicle coming to their village, all children will run happily to see which outsiders are coming today to change their life. They always welcome guests. And I experienced this many times during my participation in the ‘field works’ of the NGO.

At the afternoon, the children of the Muslim village ran cheerfully towards a truck coming. This truck is a special vehicle made for desert transport. It is called as ‘kekra’, now no longer produced. The kekras are the king of desert, replacing the camels which are frustratingly too skinny now after the long drought. The kekras brought water and workers to this village. The government decided to build a school nearby, and the materials are coming today. The workers are staying in the same otagh as I do, but they prefer to sleep on the floor or outside. The building of the school is supposed to finish in three months, but as commonly in Pakistan, whether it is going to finish or not is another question. Not to mention in deep desert like this, in the biggest city of Karachi there are many unfinished buildings due to mismanagement.

The children were excited to see the modern vehicle

The government of Pakistan works hard to build infrastructure in villages in deep desert like this. This is something that should be praised. But infrastructure is not enough. Many schools they built become merely buildings with desks and chairs, but no teachers and students. What is the meaning of school without teachers and students? The school buildings turn to be meeting point or community hall for the villager men, to pass their boring day by chatting around. Teachers usually come from the localities. Their education is also not high. And students? Even that education is free, the parents don’t want to send their children to school. In one interview with a parent who don’t want to send his children to the school, he said in energetic motion, “We are illiterate, why should our children be educated? They have to be like us. They have to be like our ancestors!” In my humble opinion the government should teach the parents first. But who will teach the government, argued someone.

Education can be still exists without the buildings and benches. Teachers and teaching material, also the motivation of students are the most essential things at this moment. Hopes, as what the village children are waiting for, are not something should be waited. Hopes should be created. But these children might need some more time to start to build their hopes and dreams.

New school = new future?

Two nights in Ramsar for me were days full of learning. I also experienced the hard life their life, taste the same water that they drink (it contains sand, dark coloured, and has strange taste), slept in their way (with animals around), passed the time together. And when it came the time to leave Ramsar, I felt both relieved and sad. Relieved because I may return to the town and enjoy life with plenty of water to drink, sad because I had to leave the laidback life of the village in this deep ‘jungle’. The 75 minutes bus journey to Ramsar was packed by almost the same traders, now filled with sheep and goat to be sold to the bazaar of the town. And the ticket collector just refused my payment, merely because I was a guest (mehman). Despite the hardship of live, despite the desperate need of money, hospitality (mehmannavazi) is still something that they are rich of, and they should be proud of.

Membaca ceritamu di atas, saya jadi bersyukur sekali bisa tinggal dan hidup di tanah yg subur seperti Indonesia dgn segala kekurangan dan kelebihannya. Tapi klo Indonesia ga dijaga tanah yg subur juga bisa jadi gersang. Beruntung kamu bertemu orang-orang yg baik hati di sana.

Salam,

Maria