Adventurer Agustinus Wibowo: A journey home

- By Rory Howard China.org.cn, May 8, 2015

Agustinus Wibowo is a Chinese-Indonesian author. At first glance, he seems more like a traveler than an adventurer and more like a happy conversationalist than a philosopher. But just as my first impression of him is challenged by what I learn of him in our conversation, so too do we find in his latest book, “Ground Zero: When the Journey Takes You Home,” that his sense of self has been tested by his upbringing, his culture and his travels.

Danger, charity, humanity

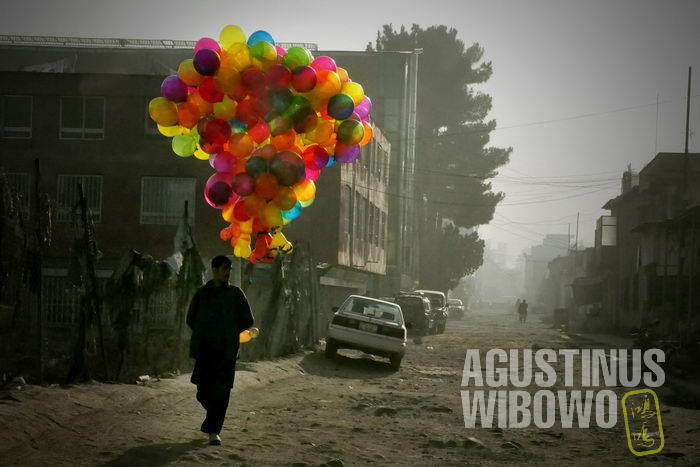

Wibowo’s first two books – “A Blanket of Dust” and “Borderlines: A Journey to Central Asia” – tell of his earlier travels through Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. When asked what took him to these places, he answers that his journeys were governed by chance. “I wanted to be a journalist, but I didn’t have a background in journalism. The road itself is the best university,” he says.

His journey began in China, the “land of his ancestors,” where he studied computer engineering for many years in Beijing before becoming disillusioned by education. He had no interest in pursuing a career in his field, so he decided he had to travel and become a journalist. It took Wibowo’s father a month to accept the idea of his son going away to become a journalist; only then did Wibowo set out.

He started his journey with little more than two thousand dollars in his pocket and a dream of travelling from Beijing to South Africa. Some ten years later, Wibowo has realized half of his dream: he has become a travel writer, photographer and journalist, but he has not yet made it to South Africa.

I asked if he was disappointed that he has not made it that far. No, he says with a contented smile. As our relaxed interview develops, Wibowo tells me what he has seen and learned, and he hints at why getting to South Africa is less of a journey than the one he has already taken.

He frequently stood on the knife-edge of danger. He travelled over mountains in rickety cars at such high altitudes that lack of oxygen had him seeing stars. He lied to police about being a Chinese national in an attempt to get into Tibet (every foreign traveler who plans to visit Tibet is required to have a travel permit issued by the Tibet Tourism Bureau), but his scariest story is about almost being kidnapped.

“In Afghanistan, I was almost kidnapped by a taxi driver,” Wibowo tells me, his smile unwavering. “Foreigners aren’t supposed to take taxis, but I wanted to save money. The guy asked for twenty dollars. I didn’t have twenty dollars. He drove the car all the way to the mountains.” As the dramatic situation unfolded, Wibowo drew on his knowledge of Islamic society in Indonesia in the hopes that reciting Muslim prayers out loud might save him. “Did this help?” I asked.

“No. The taxi driver said he would become Muslim again after I gave him the money.” The offer of a hundred dollars was enough to get the driver to turn around. Not that Wibowo paid up. He waited till he was in an area protected by soldiers and jumped out of the car.

In the face of danger, Wibowo reacts much like some of the real-life characters in his books who live in peril. He treats the experience as a joke. “I phoned a friend and told him about what happened.” He laughs. “My friend told me that I had robbed the taxi driver. I didn’t pay him any money!”

Wibowo has seen surprising reactions to stressful and harrowing situations throughout his travels. He recalls bombs going off in Kabul when he worked there as a photojournalist. “By the afternoon everyone is smiling again. Like nothing happened.”

He also experienced this before his travels began. In the wake of the 2004 tsunami, Wibowo, then in Beijing, collected money to buy necessities for people in affected areas of Indonesia.

“What I thought I would see was desolation, hopelessness, tears…However, sitting in the refugee camps to hear their stories, everyone was telling about how the water was higher than the coconut trees, how their family had disappeared, and it’s very hard to take in all these stories, but you don’t see tears in their faces!” He was taken aback that people who had endured such catastrophe and loss still had hope.

A journey homeWhen asked when he first got his wanderlust, Wibowo has multiple responses.

A journey homeWhen asked when he first got his wanderlust, Wibowo has multiple responses.

Wibowo became a stamp collector at a young age. His home is in a remote area of Java, sandwiched between mountains and volcanoes. Through stamps he imagined “exotic” places and the lucky people who lived there. “Countries put their best sides on stamps,” he says.

He recounts how he wanted to see the mythological “land of his ancestors.” Growing up as part of the Chinese minority in Indonesia, he remembers his mother constantly telling him about the people and traditions of their ancestral homeland. His knowledge of China came from books his mother read to him and from information passed on by his extended family and the general community. His mother and her ancestral land are the focus of his latest book, and coming home is his latest journey.

In “Ground Zero,” Wibowo sits at his mother’s side as she lies dying from cancer. He tells her stories of his travels through China in the same way that Scheherazade read stories to the king in “One Thousand and One Nights.” Much like the storyteller in “One Thousand and One Nights” who hopes to prolong her own life for one night by telling the king interesting stories, Wibowo hopes to save his mother by reading to her from his personal travel diaries.

The book also tells of a journey of self-discovery. Wibowo tells me he feels part of a special group of people – the Chinese. His mum, who did not visit China until her later years, created a legend in which Wibowo has lived.

“I remember that I spat in the street and my mum hit me. ‘Indonesians spit! Not Chinese!’ She said.” This idea was quickly shattered when he arrived in Beijing and saw many people spitting in the street. China felt less like the home he had envisioned.

“They charged me the same prices as they charge Americans,” Wibowo says. He felt like an outsider amongst the people of his ancestral land, and he lacked a sense of belonging, since they weren’t willing to accept him.

But then he developed a similar feeling about Indonesia. One day, when he applied for a visa, he discovered that due to mistakes in his paperwork, he was not an Indonesian citizen and was technically a stateless person.

The story behind this is the persecution of the Chinese under the former Suharto regime in Indonesia. “Chinese-language books fell under the same category as pornography and ammunition on the customs declaration form you filled out on the plane,” Wibowo recalls. As he relates the stories of his journeys to his mother, he tries to piece together his origins and discover where he belongs. Does he reach a conclusion? Wibowo is on a constant journey that he wants to tell his reader about, even when he is in a place the reader might call home.

Augustinus, I enjoyed this mature and well argued analysis of Jokowi’s presidency and of the Indonesian populace’s reaction to it and to previous presidencies. In terms of the reading of books I see the germ of change happening in (at least) Jakarta now. There is a huge desire for practical knowledge and people are obtaining it not only from books, but from on-line sources. There is still a long way to go in terms of critical thinking though, not least because of the passivity of the average Indoensian. But with unevidenced opinion proliferating on line, perhaps these skills will grow, by necessity. I hope you continue to write informative nd thoughtful articles such s this one. Best Regards

Graeme Maher