Port Moresby 20 August 2014 Flying with Air Niugini

“One thing you have to remember is,” said one staffer in Indonesian Embassy in Port Moresby, “PNG is acronym for Promise Not Guaranteed. Never think that by holding a valid flight ticket you are guaranteed to fly.”

Last week, Indonesian and PNG government held an annual border meeting in Port Moresby. One Indonesian delegation of 40 people was departing from Jayapura and crossed the land border to Vanimo in Papua New Guinea side. From the northern city, together with the Indonesian Consulate delegation, they were supposed to take domestic flight with the national carrier, Air Niugini, to Port Moresby. But once they arrived in the airport, they were told that the flight they were taking had no seat left. All of them held a confirmed ticket, but they were refused to fly. Worse, there were no other flights in the next three days. Thanks to assistance from the PNG governor in Vanimo, they finally made their way to Port Moresby, by chartering a special airplane!

Jacksons International Airport, Papua New Guinea (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

Today I was to fly from Port Moresby to Daru. It’s a small island which once served as the capital of Western Province, the westernmost province bordering Indonesia. Actually I planned to travel overland by hitchhiking fishermen’s boats or cargo boats or any dinghies, but I had been waiting for two weeks in the capital without any result. I really wanted to avoid flying, but it seems that I had no other option. My flight, PX 800, was to depart at 12:05. But the people in my embassy advised me to be in Port Moresby’s Jackson airport at 9:30 the latest, so I would be the first passenger to check in. They were sure it would guarantee my departure.

I was the only passenger queuing in front of Air Niugini counter for the flight to Daru, behind a woman with flip-flop. Other than her, I saw no other passengers in this non-air-conditioned hall. Maybe I just came too early.

The check in process was very smooth. I had got much time to walk around the airport hall to take some snaps. I found that they were very serious to keep this airport and their airplanes clean from betel nut liquid spat by the people; everywhere I saw warning posters reminding people not to chew buai (betel nut). Before we entered the X-Ray checking room, the officers were checking thoroughly so that nobody brings buai to the cabin. Air Niugini also announced that the carrier would not accept nor transport any luggage containing betel nuts.

The uniformed man who checked documents and boarding passes before the departure hall enquired me in Pidgin (“Broken English”), “Yu kisim foto hia?” You catch photo here?

His expression was serious. I was afraid that he would do something to the photos I had taken in this airport.

“Yu laikim mi kisim foto bilong yu?” You like me catch photo belong you? I directed my camera to him. I put an innocent face.

“No. Yu rong!”

He allowed me to pass.

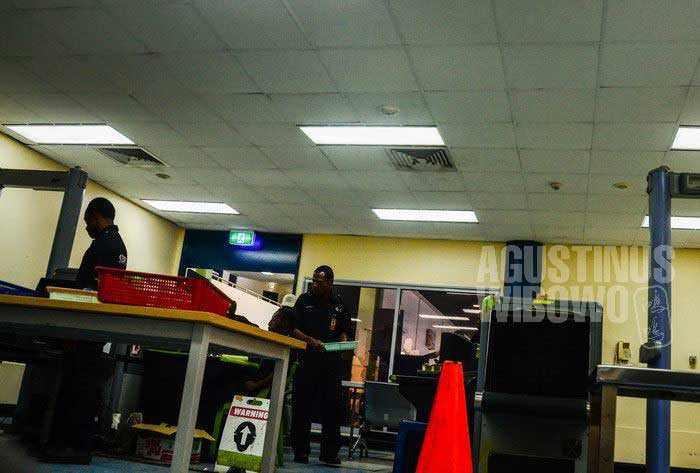

The security guards here were all from G4S, a foreign private security company. (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

The next was the X-Ray room. There were two machines, only one of which was working. There were half a dozen of workers in this room, men and women. They were wearing G4S uniform. It was strange for me that the security of the national airport of this country was taken care by a foreign private security company. One female officer saw the camera hung around my neck, quickly expressed her wish, “Bos. Yu kisim foto bilong mi?”

“Kisim foto lo hia no itambu?” Taking photo here no forbidden?, I asked.

The woman with some black round tattoos around her nose was excited. “Nogat! Kwik. Kisim!”

When I directed my camera to her, all the other male officers beside the X-Ray machine immediately shouted, “No taking photos here! The company does not allow!”

The woman with tattoo around her nose shouted back, “No problem! Wanpela photo tasol!” One-fellow photo that’s all.

They were arguing hard, shouting to each other. Finally the woman shook her head and said to me emphatically, “Bos. No ken kisim .Yu go!”

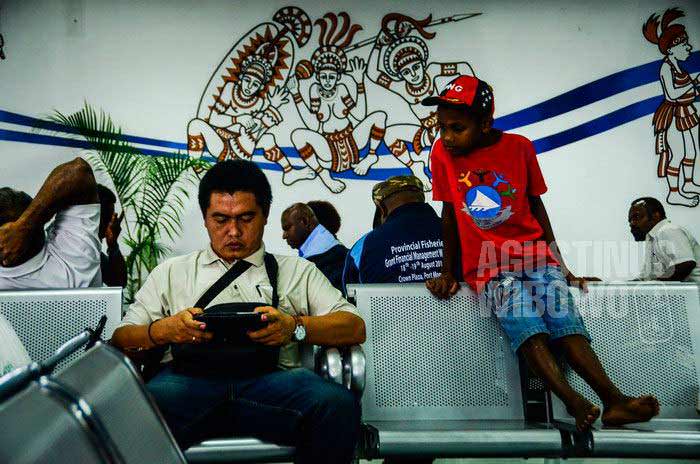

Waiting in the waiting hall (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

I waited in the departure hall right next to the X-Ray room. I was chatting with a Polynesian guy from Tonga. He was here in Papua New Guinea as a Mormon missionary, for his two year dedication of service to the Church. He said he had lost 20 kilograms of his weight as life was difficult in this country. Now he was so slim, while most of the Tongans are obese. He worked in Lae, the second city of PNG, but the danger of the raskol (rascals) was even worse than the capital Port Moresby. The Mormon missionaries are requested to always wear white shirt, tie, neat trousers. The clothing made them resemble an executive or salesman. The raskol thought they must have much money. The Tongan guy once was attacked by a raskol with handgun. Unfortunately, a missionary has nothing but Good News.

He then told me the miracles of Jesus Christ. He also gave me three booklets of their Prophet Joseph Smith. He suggested me to visit the Mormon Church in Daru.

I needed to go to toilet badly. The toilet was located at another room, across this departure hall, and I had to pass by the X-Ray checking room. The woman with tattoo around her nose stopped me. “Bos. Yu kisim foto nau!”

I was not brave enough. But she kept insisting. She then dragged me to the door in front of the toilet. “Kisim hia!” she commanded.

Click.

She told me whenever I would return to this airport, I should give that photo to her. “Wonem taim yu kambek hia?” What-name time you come back here?

“One-fellow year? Two-fellow year? God savvy!” I said.

The woman just shook her head in disappointment. “Yu go!” she said quietly.

Port Moresby is the strangest paradox I ever seen. In one side is the horror of the raskol, about the murders and robberies all over the city. But the other hand, I have never met such welcoming society like this. They were very hospitable and tried their best to help strangers. They were full of curiosity and openness in their attitude, which is said as the Melanesian characteristic.

I went back to the departure hall. It sounded that somebody was calling my name. I listened carefully. My name was called for the second time by the announcement loudspeaker. They asked me to get into my plane as soon as possible. I checked the time. It was still 30 minutes ahead from my boarding schedule. My name was called for the third time.

I was rushing to the plane. I walked through the tarmac, passed through a long fenced corridor covered by canopy. A Bombardier Q400 plane—with big propellers at its both side and using Canadian-made turboprop engine—had been waiting there. I was the last passenger boarding to the plane.

The cheerful Air Niugini flight attendants. (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

“Quick,” said the air hostess at the plane’s gate. “We are flying soon.”

“But this is not the time yet,” said I.

“All passengers are already ready, so we fly ahead of the schedule,” she said.

Flying delayed is normal. Flying before the schedule was my first experience ever.

The plane had capacity of 70 passengers, but only about 20 seats were taken. Besides explaining how to wear seat belt, the announcement before the flight also reminded the passengers not to smoke and not to chew betel nut. The flight to Daru was only 1 hour 15 minutes; the ticket for 442 kilometer distance was US$ 180. Budget flight was never be even imagined in Papua New Guinea, where domestic flight may cause US$10000 (in a country about the size of one Indonesian province). The international flight to one of its neighbor countries, Solomon Islands, cost a whopping US$800 one way.

“You are not allowed to chew betel nut in this flight!” (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

Port Moresby seen from the sky (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

After passing the Gulf of Papua, our plan crossed a strait from the mainland, heading south to reach a little island in darker color.

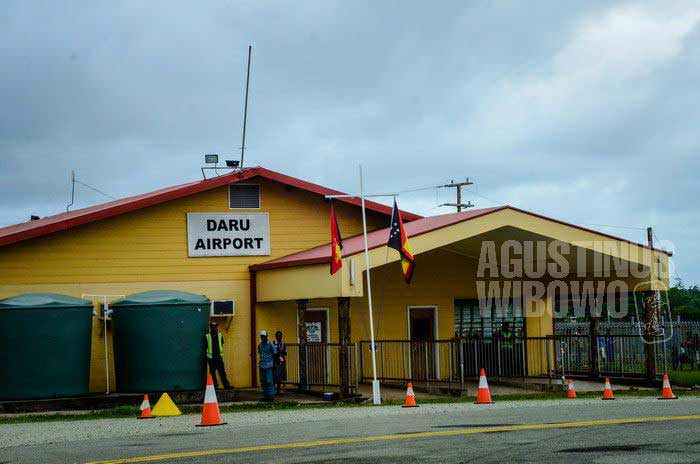

Daru. The airport looked like a football field surrounded by fences. People were standing in line along the road behind the fence, watching the landing airplane. Were they dreaming for a departure, or celebrating an arrival? Once our plane landed and we got off the plane, the number of people behind the fence was significantly reduced. The attraction was over. They have returned to their houses. The rain got bigger, the passengers were running to the airport building, which looked like a tiny pretty yellow house with two huge tank to catch the rain water.

We were waiting for our luggage. Our bags were carried one by one by the airport workers from the body of the plane to a wooden bench in front of us. Then it was our turn to pick any bag that belonged to us. Welcome to Daru.

Welcome to Daru (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

Were they dreaming for a departure, or celebrating an arrival? (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

Daru airport (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

An efficient luggage collection–just a little bit too long time. (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

***

Two weeks after our arrival, I returned back to this airport to accompany a friend of mine who was departing to Port Moresby with Air Niugini. The plane only departed twice a week, on Sundays and Wednesdays. From behind the fence, I was watching the passengers were queuing across the tarmac, walking towards the plane. The last two passengers got in the plane, but soon after that, they got off again. They were waiting for their luggage to be taken off the plane. Once they got it, they also went home. The plane finally took off. The people in the airport were clapping their hands, like celebrating a perfect performance.

I heard from the airport staff, that the two poor passengers could not fly, as the plane got excessive cargo. I asked him, what the left-behind passengers would do.

“What else they can do? They just wait for the next Wednesday,” he said.

“Won’t they get angry? In my country, if the plane delayed just for two hours, passengers would be angry fiercely. These two passengers had got their boarding pass and they were refused to fly, would not they complain to the airlines?”

“Papua New Guinea is different from any other countries,” he said, “In Papua New Guinea all people are understanding. They all understand the situation.”

Case closed.

Delays, cancelations, overbookings, all were just too often in domestic flights in this country. Mr Noweda, a local friend of mine who was a senior staff in an international NGO in Daru, once told me his experience with Air Niugini. The plane he took was full of passengers. The ground staff of Air Niugini seemingly had given one seat to his family member who failed to get seat. He then told the family member to be the first to get into the plane. Once the passenger who were supposed to take the seat came, he was arguing why there was someone occupying his seat. Each of the two passengers had boarding pass for the very same seat. The flight attendant then had no choice but to ask the passenger who came later to get off the plane, even though he was supposed to be the one rightful for the seat. “It seemed that our ground staff had made a mistake,” said the flight attendant, “Sorry.”

Listening to the story, I could not but tell Mr. Noweda about the acronym of PNG that I learned from my embassy. “It’s not Papua New Guinea, but Promise Not Guaranteed.”

“That’s brilliant!” Noweda could not help to laugh out loud. “I have to note this down!”

Promise Not Guaranteed (AGUSTINUS WIBOWO)

I’ve read your travel articles on kompas.com some years ago, and happy that I can continue reading your experience here too.